The stress of modern mammalian motherhood

Breastfeeding, formula feeding, combo feeding… oh my!

Build a kid. Launch that kid out of our uterus. Immediately start making them food… from our bodies. Mammals are amazing.

We have the capacity to liquify parts of our body and construct a balanced, species-specific, developmentally-appropriate concoction of nutrients, immunological factors, anti-inflammatory agents, growth factors, and cells (yes, cells! Breast milk passes along stem cells 🤯). All this for a newly formed creature that instinctively knows how to stimulate and extract that food out of a bunch of tiny tubes packed into our nipples. How crazy is that?!

So why is this biological wonder stressful? (she writes to the chorus of every human who has ever lactated laughing in the background…)

While I have already made the bold statement that lactation is not a stressor (and, admittedly, debating this would likely follow a similar path as this discussion with

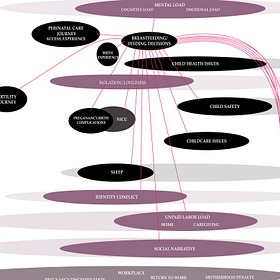

), lactating, breastfeeding, and making decisions along the entire range of feeding choices for a brand new tiny human IS stressful.The breastfeeding/feeding decision stressor node is so tangled up in the web of maternal stressors that every attempt to untangle it serves as a reminder that it truly is just that interconnected. Honestly, from the time I started writing this to the moment right before sending this out, I have added additional connections.

Let’s start by acknowledging the gappy science.

As an Animal Science major in college, I learned all about how to keep a lactating cow in positive energy balance (surprisingly difficult!). With a surface-scratch knowledge of the amount of research and funding that fueled cow → human food consumption, I found myself shocked by how little we know about human lactation and human → human food consumption.

“When we zoom in on the number of articles just investigating breast milk, we see that we know much more about coffee, wine and tomatoes. We know over twice as much about erectile dysfunction. That we know so much less about breastmilk – the first fluid a young mammal is adapted to consume – should make us angry.” – Dr. Katie Hinde, professor at Arizona State University and one of very few researchers in the world of human milk.

In many ways, breast milk is magic. And with more research filling the gaps, I expect to see even more of that magic identified.

Now if it seems like I’m leaning towards the “breast is best” camp, I want to stop here for a second. I believe that the knowledge gaps only fuel the“breast is best” vs “fed is best” debate and I want to ground this post in: you are all correct. The magic I expect from additional breast milk research is more on the “breast milk = good smelling baby poop” side rather than the “breastfeeding will make your kid a genius!” side of things1.

For this conversation, we need to acknowledge the value and importance of breast milk and breastfeeding while also accepting the stress that breastfeeding challenges and feeding decisions exposes mothers to. With more research AND shifts in the social narrative, maybe we will get to a point of “breast is pretty darn great… but NOT at the expense of the mother’s health and wellbeing.”

When we start there, we can fight for education + support and other broad solutions to limit exposure to the stressors associated with breastfeeding/feeding decisions while viewing breastfeeding/feeding decisions as a stress-inducing risk factor at an individual level.

With that starting point in mind, let’s skip over the research focused on the benefits of breastfeeding for babies and head straight to the maternal health outcomes related to breastfeeding/not breastfeeding/breastfeeding duration, etc. (Note: a majority of reported health outcomes for moms tend to focus on maternal mental health so that’s the connection we’re discussing here.)

Historically crappy priorities in breastfeeding research

For far too long, most research approached the potential link between breastfeeding and mental health from the directionality of maternal mental health → breastfeeding challenges with reported outcomes linking perinatal depression with lower breastfeeding duration and reduced “success”. This directionality probably stems from the tendency to over-prioritize baby over mom and the lopsided circle of maternal health → child health → maternal health that I’ve noted before.

Another weakness of concentrating research questions around this focal point is that most studies only include exclusively breastfeeding participants and only capture time points at the very beginning (initiation of breastfeeding) and the acceptable “end” (six months of exclusively breastfeeding) – examining these two timepoints as quantifiable metrics for breastfeeding failure. With “failure” from the perspective of baby’s needs only within a confined definition that breast milk and breast milk alone is what baby needs.

For example, a literature review2 on this from 2015 combed all available, sufficient, on-topic studies from 1983-2013 (48 in total) and when the authors describe the purpose of their review, they state: “Most countries do not reach desirable rates of exclusive breastfeeding initiation and exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months. Pregnancy depression and postpartum depression appear to be possible significant contributors to this issue.” The authors also boldly point out their goal is “a systematic review of the literature on the association among breastfeeding and pregnancy and postpartum depression.”

See the problem here?

And that’s why I won’t be discussing that paper. Or pretty much any other study falling in this category (and there are a lot).

Another approach: breastfeeding → maternal mental health

Another review from 2022 luckily took the opposite approach: what are the effects of breastfeeding on maternal mental health.

The authors started with 1,100 articles turned up by searching databases for key terms. Narrowed their full-text review to 339 articles and ultimately included 55 studies in their analysis. The authors conclude that:

“Overall, breastfeeding was associated with improved maternal mental health outcomes. However, with challenges or a discordance between breastfeeding expectations and actual experience, breastfeeding was associated with negative mental health outcomes. Breastfeeding recommendations should be individualized to take this into account.” – Yeun et al. 2022

On the association between breastfeeding and negative mental health outcomes, the reviewed research includes3:

Eight studies reporting potential links between breastfeeding challenges and mental health outcomes.

Seven studies suggesting that the stress and guilt associated with an inability to breastfeed or the choosing not to breastfeed may contribute to elevated risk of postpartum depression and anxiety

Five studies including discussion of self-efficacy or confidence in ability to breastfeed and how infant feeding decisions relate to mental health outcomes.

In addition, the authors point out that, while oxytocin (released during breastfeeding) is awesome for anxiety and stress reduction, the benefits of oxytocin may depend on the breastfeeding environment. Chronic stress related to breastfeeding challenges can disrupt the typical role of oxytocin and muck up its positive effects on modulating maternal mood. Yes, oxytocin, the love hormone, the favorite go-to-hormone when making a “it’s good for mom’s health!” case for breast is best also has a dark side when it comes to breastfeeding challenges.

Considering all the angles, the authors make the following suggestion:

“Breastfeeding recommendations must be individualized and consider the potential negative impact of breastfeeding challenges on maternal mental health. In such situations, recommendations may include discontinuing breastfeeding.” – Yeun et al. 2022

The “bad mother” narrative

Now, let’s add in guilt and shame and the “bad mother” social narrative that drills itself deep into our inner conscience. This feels like a connection point that adds a specific layer to breastfeeding/feeding decisions because it affects how we feel about the choices we make (or are forced to make). Personal interpretations of “success” and “failure” may affect the degree to which our stress response system responds to breastfeeding challenges.

Though not as well studied from a maternal health outcomes perspective4, there is a growing body of data connecting feelings of guilt with stress and negative mental health outcomes from research on PTSD symptomology, caregiver distress, healthcare worker burnout, and repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic. As stressors, guilt (defined as an self-conscious feeling of having done something wrong) and shame (similar to guilt but internalized with the added feeling of “failing in front of others”) carry the key element of lack of control when it comes to triggering the stress response pathways that affect our health.

As it relates to breastfeeding, a literature review from 2021 that included 21 articles from 1997 to 2017, looked at categorizing “guilt and shame” experienced for both breastfeeding and formula feeding5. As the authors point out, guilt and shame were both associated with how individuals perceived themselves as “bad mothers” but the specific feeding method added nuance. Mothers experienced guilt more often when exclusively formula feeding as compared to combo feeding or exclusively breastfeeding (the review lumped combo feeding participants with exclusive breastfeeding participants due to paucity of studies). Importantly, this measurement of guilt was stronger when an individual’s intention to breastfeed, set during pregnancy, did not follow expectations.

From that review, the authors constructed a framework on the way guilt and/or shame were experienced based on the synthesis of study result themes:

Guilt was the biggie here (with “shame” far less studied) and the sources depending on feeding method. Breastfeeding mothers experienced guilt in relation to family and peers; formula feeding mothers experienced guilt in relation to healthcare providers and peers.

Let’s talk solutions

The above analysis of this potential stressor on the map only scratches the surface, of course. I could probably dedicate this entire project to this topic alone, but, we gotta keep moving!

Yes, the breastfeeding/feeding decisions stressor node can be potent.

It is layered. It is personal and yet, also, universal. It is interconnected on multiple levels.

As you can probably expect from everything to this point, a key solution is support without judgment – in healthcare, at home, in the workplace, amongst friends, in social media feeds. Language matters. Tailored care and approaching breastfeeding challenges with a balance of mental health care and support for all feeding choices is critical.

In the next part of this series, I go deeper with an expert in this space,

, CEO and founder of SimpliFed, to get eyes on the layers of the problem and key solutions that squarely address the elements of stress related to breastfeeding challenges and feeding decisions. I spoke with Andrea about her personal experience (currently breastfeeding her third kid!), her professional insight, her views on connections with the breastfeeding/feeding decisions stressor node, and her “in a dream world…” views for the future."Breastfeeding and baby feeding are connected to all of this"

From a biological perspective, breast milk is a wonder.

From a stress perspective, that statement alone can be a trigger.

How do we tease apart the stress related to breastfeeding and feeding decisions in the broader context of maternal health when it is so intertwined with societal expectations and narratives, and, far too often, lack of true “choice”?

From that discussion, I dive into the stressor map to examine the connected stressor nodes that add to breastfeeding challenges + feeding decision stress as well as identify additional key solutions that can remove, alleviate, and/or buffer that stress.

Reducing the stress of modern mammalian motherhood

When it comes to breastfeeding and baby feeding decisions, the stress is layered, the connections are personal and, somehow, also universal.

Quick note about subscriptions: The Maternal Stress Project is an educational and idea-spreading initiative and I want it to be available to all. You can subscribe for free and get all posts delivered right to your inbox. However, if you feel compelled to bump up to a paid subscription, your generous support will facilitate the growth of this project… and be much appreciated!

Sharing and spreading the word is equally valuable and appreciated!

Obvious oversimplification but you get my gist. Honestly, the (very personalized) reason I prioritized breastfeeding for my own babies was because I found it cool that digestion of this food source was so efficient that their poop smelled like butter. Also, I hate washing bottles and my memory and diaper bag packing skills were shit so I appreciated having a failsafe food-on-demand option. Oh, AND I had support without judgement and didn't face extreme challenges. So, grain of salt.

I prefer literature reviews to individual studies because when you’re relying on single studies, you can find a paper to justify whatever you want. And research is not wholly unbiased – if you're going to study the positive effects of breastfeeding, there might be some self selection in the sample or you might flatten the results with averages, or you might not publish at all if you get negative data because no one likes to publish negative results. We can go into the bias of science and science reporting but… save it for another day.

All references can be found in review article — https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/jwh.2021.0504

But if you know of any studies or are a researcher studying this, please let me know!

A couple limitations worth noting for this review. One, this study was mostly based on qualitative (descriptive) data because quantitative data on the subject were sparse. Two, for the research reviewed (and a good majority of human research, in general) – participants do not accurately reflect the human population, with a tendency to skew recruitment towards white, educated, cis, partnered women with higher socioeconomic status.

This is a fantastic piece full of research Molly. And that bit just summarises what I tend to discuss with women in my practice when breastfeeding itself becomes a stressor (aka, the best thing out of all, is mum's well-being!):

"'breast is pretty darn great… but NOT at the expense of the mother’s health and wellbeing'.

When we start there, we can fight for education + support and other broad solutions to limit exposure to the stressors associated with breastfeeding/feeding decisions while viewing breastfeeding/feeding decisions as a stress-inducing risk factor at an individual level."

So glad I found this article! I had severe postpartum PTSD and felt VERY pressured to breastfeed, which contributed to my exhaustion and sleep deprivation in the hospital (I spent a week there with HELLP syndrome and a full-term but underweight baby in the NICU). Things would have been so different had I been told by a kind nurse, "hey, your body is very sick and it's going to take a long time to recover. your best decision may be to formula feed so your family can help take care of feedings and you can prioritize sleep. producing breastmilk right now does not need to be a high priority and you can bond with your baby as you have energy."