Centering around pregnancy, Part Two: Why does physiological flux matter?

Pregnancy is both natural and risky -- a model for physiological extremes

As the title implies, this post is a continuation from Part One, which you can find here:

To summarize that post:

1. The physiological changes during pregnancy are awesome and I am slightly obsessed with their awesomeness and want to share that obsession with the world;

2. As reflected in the current map of stressors – I am considering pregnancy as a model for a period of physiological flux that also aligns with specific stressors related to gender, parenting/caregiving. This allows some degree of extrapolation to other, less appreciated and less studied, periods of physiological flux for the cycling + caregiving body.

Onward!

By its very nature, pregnancy is both natural and risky. Neither side should dominate our view of this stage of the human experience. I say this with love and in an attempt to unite those who dedicate their lives to perinatal care and the health of pregnant people. It is also important accept both sides for the next stage of this discussion.

I’m going to be a little lazy here and use my own published words from a 2020 academic paper to put this in the context of homeostasis, a core concept when discussing physiology:

“Homeostasis is the biological concept that every physiological up is met with a physiological down to counterbalance and bring the body back to a steady state. A body out of homeostatic balance is prone to disease. Pregnancy and early postpartum represent a unique homeostatic state in a woman's body— in balance yet pushed to an extreme.”

To me, this is the most incredible thing about pregnancy – most pregnancies exist in an extreme physiological state yet remain quite healthy. A healthy birthing parent. A healthy baby. A healthy postpartum return. The pregnant body is pushed to the absolute physiological edge with a good chance that it will navigate the intense, rapid internal shuffle without negative health issues.

But that is not the case for all. Modern medicine undoubtedly improves health in so many cases and has saved the lives of countless babies and mothers.

Both are true.

It is normal for a body to undergo all the changes and remain healthy with no medical intervention; and it is normal for a body to undergo all the changes, be pushed too far, and require clinical support. This is why pregnancy is often marked by an elevated risk of mental health disorders, cardiovascular disease, metabolic dysfunction, immune conditions, etc.

That elevated risk is also normal. Remember the seesaw analogy from the Stress 101 post? We have a similar situation here when it comes to homeostasis during pregnancy.

The pregnancy seesaw represents the balancing act of all the systems and mediators and hormones that keep the body in balance while everything rises or falls to levels that would never naturally occur in a healthy, non-pregnant body1.

Here is how I see that seesaw analogy as it relates to pregnancy: no pebbles here, it is more similar to building a house of cards on top of the seesaw:

I prefer this analogy because it is both delicate and well mapped out. Our bodies know how to do this.

BUT just because the human body knows how to do this does not mean that it doesn’t go wrong every now and then. Maintaining homeostasis during this time is tricky. Tricky to stack the cards just right, tricky to balance all the added weight, and then extra tricky to dismantle the house of cards as the body returns towards pre-pregnancy levels while continuing the work to keep balance2.

A body in balance is a healthy body… on the outside. But that doesn’t mean that it isn’t close to tipping.

This is why we also need to normalize the ‘things go wrong’ side of pregnancy as well, especially as it relates to peripartum mental health — the most common health complication during this time.

actually quoted me better than I could quote myself when she was in a conversation with about this exact topic:“she told me ‘it's a fucking miracle’ that anyone gets through this process without having some symptoms of postpartum mood and anxiety disorders solely based on biological factors (not even taking into account the societal factors!)”

(Side note: the ‘she’ is me. And, yes, I do have a tendency to drop F bombs in interviews. We call them ‘adult punctuation’ in our house. Discussions on maternal health often deserve some adult punctuation.)

Going deeper

I want to emphasize something: Pregnancy is NOT a stressor3. Postpartum return is NOT a stressor. Lactation is NOT a stressor. And none of these states represent illness. These are natural processes in the human body that sometimes tip that body off balance, naturally, and lead to illness.

Pulling from that 2020 paper, referenced above:

“pregnancy itself is not a disease state, we do not consider pregnancy itself to be a stressor or a major contributor to allostatic load or wear-and-tear”

I have a long, way-too-academic theoretical model that I am drawing this statement from while attempting to spare you all from getting too into those weeds. Maybe it’s unavoidable. Here it is if you want to read it. For those who choose to avoid that special kind of torture, my attempt to summarize is this:

All the systems in our bodies (think cardiovascular system, metabolic system, immune system, etc.)4 have a normal range of set points. All the mediators and modulators within those systems work together to keep that system in within a baseline range.

There are other ranges that relate to how the body responds to challenges and maintains/returns to homeostatic balance. There is a range related to responding to predictable challenges. There is a range related to responding to unpredictable challenges.

Baseline = sustaining life

Predictable challenge = normal, necessary daily activity.

Unpredictable challenge = an acute stressor.

Example —

(Brain melt warning: feel free to stop at any point, it only gets more science-y from here)

Take the metabolic system and glucose regulation5.

Baseline = We need glucose in our blood at all times.

It is the energy source for all of the cells in our body, including our brains. We have specific hormones and all their little helpers, the mediators and modulators, working around the clock to maintain a specific range of “fasting glucose levels” so that all the cells have what they need to go about their day, but not too of it much because that is also bad.

Every now and then, the body responds to stimuli that cause the system (in this case, glucose regulation) to jump outside of its baseline range. These stimuli can be predictable or unpredictable.

Predictable stimuli = eating a meal.

You need to eat food. When you eat food, glucose goes up in the bloodstream. Then insulin swoops in and ferries that glucose into cells for immediate use and/or packs it away for later use. This is overly simplified, of course, but the key point here is the everything regulating glucose responds to that meal in an orchestrated way that is grounded in its predictability.

In pregnancy, the body still responds to the predictability of a meal, but the range of that predictable response has changed. All of the mechanisms in charge of the response have shifted amongst the chaos of prioritizing the construction of a new human. In this example, the demand for glucose for mom and baby increases and all the signals that regulate baseline glucose and meal processing shift to accommodate these new needs. In addition, the dramatic hormone changes running alongside this shift impact insulin’s ability to do its job effectively. The metabolic system continues to seek homeostatic balance, but sometimes it goes off track. It really is no wonder that gestational diabetes – related to insulin insensitivity – occurs in up to 10% of all pregnancies. Honestly, it is a fucking miracle that a majority of us make it out of pregnancy without becoming diabetic.

Without going down the line of every physiological system, the respective changes related to pregnancy/postpartum needs, and potential for negative health-related outcomes, hopefully this example paints the picture of other connections across the body — hormone changes relate to mental health disorders, cardiovascular changes relate to cardiovascular disease, immune function changes relates to immune disorders, etc. (see footnote 4 for additional examples and a handy table).

Even considering this, pregnancy is still a natural process in the human body that sometimes tips that body off balance, and leads to illness6.

Not all pregnant bodies will tip. Most won’t. But all pregnant (and postpartum) bodies are closer to tipping. And this point becomes relevant in the context of unpredictable stimuli (aka stressors!)

Will tackle that one in the next post:

Centering around pregnancy, Part Three: What does this have to do with stress?

Wrapping up the series on why the maternal stressor map centers around pregnancy with… STRESS! This post is a continuation from Part Two. I highly recommend starting there if you’re catching up: And if you want to go all the way back to the beginning, Part One is here:

You can also brush up on your Stress 101, if you are so inclined:

Quick note about subscriptions: The Maternal Stress Project is an educational and idea-spreading initiative and I want it to be available to all. You can subscribe for free and get all posts delivered right to your inbox. However, if you feel compelled to bump up to a paid subscription, your generous support will facilitate the growth of this project… and be much appreciated!

Sharing and spreading the word is equally valuable and appreciated!

My favorite physiological balancing act, of course, is the dance of cortisol and all the mediators regulating the effects of cortisol. Cortisol reaches INSANE levels during pregnancy. If you took a blood sample from a pregnant person, passed it to a clinician, and didn't tell them it was taken during pregnancy, that clinician would likely expect to also see symptoms of Cushing’s syndrome. One cause, Cushing's Disease, relates to having a tumor sitting on your pituitary causing the adrenal gland to continually pump out cortisol, unchecked. The pituitary isn't getting the signal to stop egging on the adrenal. This is kind of what the placenta is doing during pregnancy -- releasing its own stimulatory factor that tricks pathways leading to the adrenal, resulting in ramping up cortisol release to ⚡️EXTREME⚡️ levels (couldn’t help myself).

The high cortisol related to Cushing's is terrible for the body. High blood pressure, cardiac disease, weight gain, infection. All things you would expect from high, unchecked cortisol (which also tend to align with chronic stress!)

BUT, the same concentration of cortisol in a pregnant body does not cause these health effects (yes, some of these symptoms occur, but they are not likely related to high cortisol). Why is that?

Well, there are a lot of other things that can change in the body to impact how the cells receive and listen to cortisol in the bloodstream. When you change those pieces of the puzzle, cortisol in the blood looks a whole lot different to individual cells.

This is where the balancing act of assembly and disassembly comes in -- the more small pieces you have to change to maintain health in the face of a massive shift in one hormone, the more small pieces you have to shift back in order to ensure that hormone works effectively on return to baseline. At the end of pregnancy, cortisol drops back down very fast because its main stimulatory organ, the placenta, is gone.

If you want to dive further into this crazy world of cortisol during pregnancy and the potential connections to postpartum depression (and allllll the things we don’t know), here is an article I co-authored with Dr. Jodi Pawluski.

If your instinct when I use the word “balance” to describe homeostasis is to align with the language used in wellness culture, reset your thinking. Balance in the context of homeostasis has nothing to do with external control over the seesaw. The human body is amazing and it knows how to balance itself. If the body is truly “off balance” it could be a sign that something is actually wrong. In which case, seek medical advice, not Goop recommendations.

Even in the cases of substances that affect systems in ways similar to the molecules already inside our body, I don’t believe in our ability to use a supplement or magic potion in a perfectly titrated way to correct an “imbalance”. We do not have a molecular-level view into every cell in our body. We cannot see what else is changing in response to our mucking about. Even if something appears, on the outside, to work wonders, what did you change on the inside that will come back to bite you in the butt when your body adjusts or you stop taking that magic potion? With that said, sometimes we do need external intervention and for those occasions we also need more research (e.g. the estrogen yo-yo of imbalance during perimenopause and menopause).

I should note that I also fully support the Placebo Effect (no shock here – I believe it operates through stress pathways) so, if having that special drink to balance your hormones doesn’t really affect hormones and it makes you feel more in control and less stressed, drink it.

Spoiler for the bonus post. Now you know my stance. If my stating that “pregnancy is not a stressor” feels controversial to you, or if you feel yourself bristling at that assertion, please join us in the conversation for the bonus post.

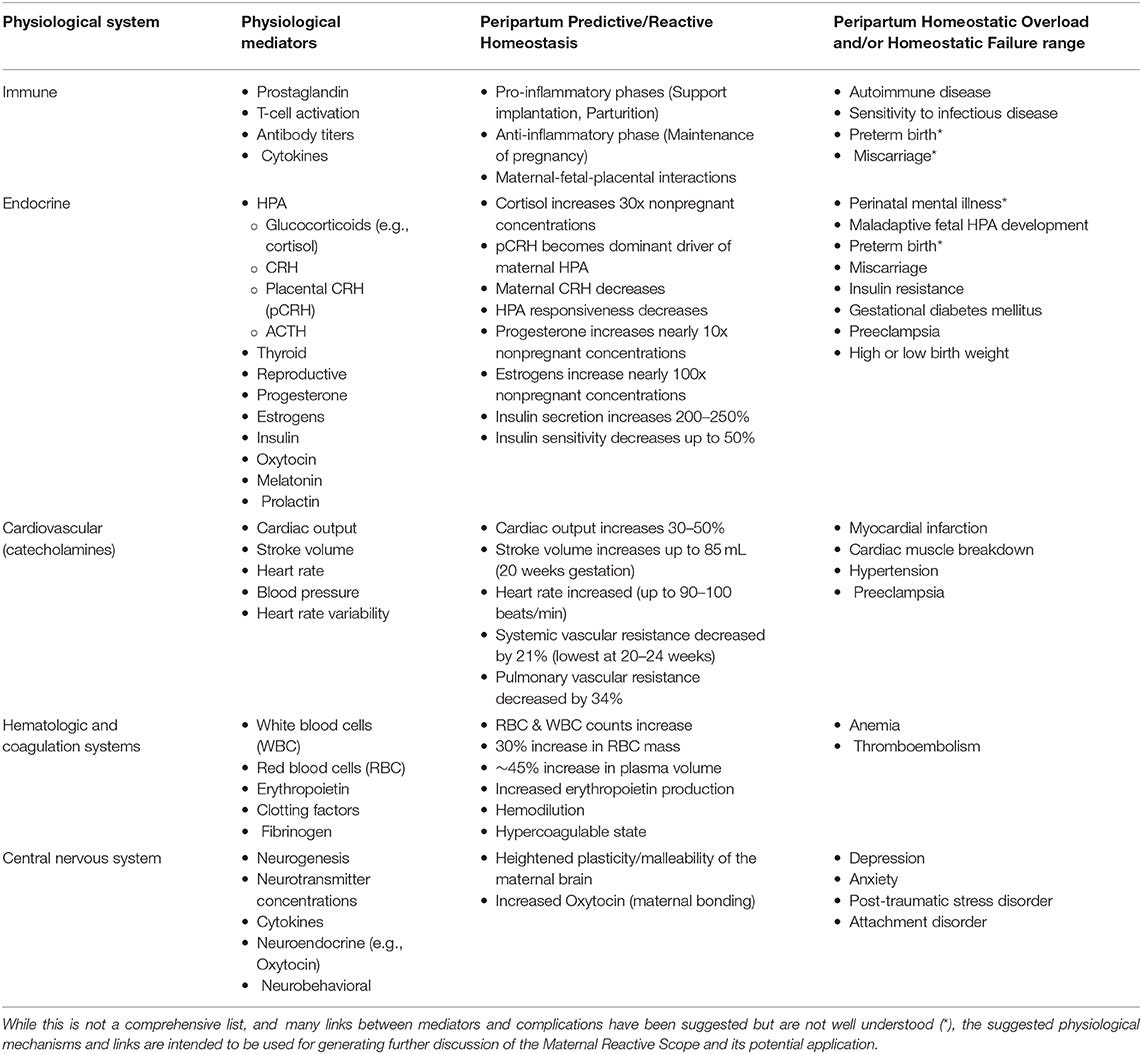

If you’re medically minded or generally curious about the biology of it all, especially when it comes to the term “mediators” and how all of this extrapolates out across physiological systems, here is a table from our 2020 paper.

Note: predictive/reactive homeostasis = healthy response to physiological challenge of pregnancy; overload and failure = illness/complications related to those changes, lack of appropriate changes, and/or chronic stress:

I am not an an expert in the metabolic system and providing my surface level understanding here. If you are an expert in the metabolic system and I totally botched all of this, please let me know!

Gestational diabetes is similar to Type 2 diabetes. Our bodies did not adapt to the modern human diet. Many of us pummel our bloodstream with glucose spikes one after another that, in many cases, our bodies still handle with impressive dexterity. However, in some cases, when the body responds to glucose spikes over and over to a point where the system has adjusted and adjusted and insulin+helpers are no longer effective at their jobs, you start to see illness – Type 2 diabetes. Type 2 Diabetes relates to insulin insensitivity. Insulin and its helpers were pushed outside of their normal capacity and glucose stays high in the bloodstream. That causes problems.