Confession. I have a tendency to keep tight definitions of “stress” and “stressor” in my head. Then I just assume everyone else is on board with those definitions. Maybe you’ve noticed?

When I first sent

a draft of the “Centering around pregnancy” series, she immediately called out my assertion that “pregnancy, itself, is NOT a stressor.”Catch up on the series of posts here and see if this statement irks you too:

After commenting on the draft with an “isn’t it though?” each time I noted that “pregnancy is not a stressor,” Chelsea called me: “This is easier to discuss over the phone.”

We spent nearly an hour attempting to convince each other of the side we were taking on this issue. After hanging up, we continued the debate by texting back and forth and sending off “a few quick thoughts” via email.

Assumptions are meant to be challenged. Holes are meant to be poked. This project is in a hypothesis stage with a lot of testing and learning to go.

Since you are here, reading and following along during this stage, we figured you might appreciate the debate. We started over in a Google doc, volleying responses and diving into the messy messiness of it all.

We would love to hear your perspective on this debate, too. Please comment, challenge, and poke away!

Here is our back and forth:

CHELSEA: I agree entirely with the statement that pregnancy is not a disease state. And I understand the importance of differentiating the fundamental processes of reproduction from outside stressors. Still, my mind recoils from the statement that pregnancy is not a stressor. This may be a rhetorical problem more than anything, but no less important, I think.

The feeling of stress is part of the experience of pregnancy for so many people—in getting pregnant, trying to do all the right things while pregnant, anticipating childbirth and new parenthood, experiencing childbirth, coping with any complications or trauma, for the birthing parent or the baby, and more. I felt a lot of what I would describe as stress, for example, when I learned that I would have to be induced during my first pregnancy.

Can you break it down—how can pregnancy not be a stressor, when stress is so common during pregnancy?

MOLLY: You just said it yourself! Stress is common during pregnancy (and postpartum) because of all the elements you pointed out. There are stressors strongly associated with this phase of life.

Pregnancy, the physiological changes themselves, are not directly related to the stress response system. Therefore, pregnancy is not a stressor.

Being pregnant exposes you to new stressors.

The stress of being induced is not an inevitable part of pregnancy. When it is seen through the lens of potential stressors during pregnancy, we can start to reassess the importance of only inducing when induction is absolutely necessary. Putting that dream aside, the way the news is delivered can also be what triggers the stress response. Add in lack of education and preparation for that outcome, and/or lack of control when medical decisions are out of your hands. There is also the unpredictability of having an expected birth story go in a different direction that you had not mentally prepared for.

What triggered your stress at that moment?

CHELSEA: My flood of tears and overwhelm were triggered when the doctor broke the news, and all of the external factors you outline above were at play. But the induction was triggered by my high blood pressure.

Gestational hypertension occurs in up to 10 percent of pregnancies—it is not uncommon. I never had an issue with my blood pressure previously. I didn’t have any of the major preexisting risk factors. And I wouldn’t have had high blood pressure in that moment if I wasn’t also pregnant.

It feels like a chicken and egg problem—how do you separate the stressor from the pregnancy?

This seems especially tricky when we consider the stress response. Isn’t pregnancy related to the stress response system?? In reporting Mother Brain, I learned so much from you and other researchers about just how dramatically the stress response system is changed by pregnancy—cortisol levels skyrocket but the body’s stress reactivity is blunted by production of a special protein that essentially deactivates some of that excess cortisol and by changes in key receptors that affect the activity of the HPA axis.

Just about every system of the body is changed, pushed to the max—dare I say, stressed—by pregnancy in ways that would not occur outside of pregnancy itself.

MOLLY: Woof, multiple things to tackle here!

I do want to acknowledge that I absolutely feel for you in that moment of tears and overwhelm. We need to give more attention to the emotional load that is carried when it comes to birth and birth expectations changing course.

Now, onto tackling your points. I’ll start with the first:

Yes, absolutely, gestational hypertension is not rare and it is related to the physiological changes during pregnancy. BUT it does not mean pregnancy is a stressor.

The science is just starting to get into all of this (don’t get me started on that) and I’m not an expert in this space. But my understanding is that one of the causes underlying gestational hypertension (especially when you have no prior history of high blood pressure) is related to the remodeling of spiral arteries delivering blood to the placenta and, therefore, the baby. This remodeling is not always perfect. And when it isn’t perfect and everything else regulating blood flow (including ramping up blood volume through a myriad of additional inputs) is firing on all cylinders to get that baby growing and ready for expulsion, pressure builds up in those pipes. It’s a part of pregnancy that is natural and normal and necessary, but it is complex and it can go wrong.

Because of this, pregnancy, itself, is risky and related to negative health outcomes. But not because pregnancy is a stressor. These problems are not caused by triggering the stress pathways (that can also happen with exposure to stressors, and, in those cases, that stress exacerbates the underlying conditions that have already made the body vulnerable). The problems are caused by the natural changes in pregnancy going slightly off course.

On that note – pregnancy overlaps with the stress response system and its pathways but it doesn’t tap into it in a way that makes me categorize it as a stressor.

I define a stressor as something that triggers an acute stress response. The physiological changes during pregnancy do not trigger an acute stress response. If they did, we’d be in a positive feedback loop that would almost certainly result in the death of every pregnant woman ever. Evolution ends there.

Cortisol levels skyrocket because it is a very important hormone when it comes to growth and fetal development as well as birth. The placenta becomes a powerhouse endocrine organ driving that rocket. There are changes in proteins and receptors and elements of the HPA axis that functionally minimize the effects of the insane amounts of cortisol cruising through the bloodstream.

Yes, pregnancy is certainly messing with elements of the stress response system but that does not make it a stressor.

Physiological changes of pregnancy alter the mediators and mechanisms used in the stress response system in order to accommodate a new physiological game of twister (maybe not the best analogy). It is not altering things in response to a single, acute event.

Pregnancy does push the body to the max, sometimes over, and this never happens any other time outside of pregnancy. However, this event happens in every body that has created every human on this planet all the way down the ancestral line. The demands of pregnancy shift the range for all the systems maintaining homeostasis (including pathways also used in the stress response). The physiological needs of pregnancy are predictable. The new range, the push to the max, is predictable. A stressor, by definition, is unpredictable.

CHELSEA: So this is where you really lost me during our phone call.

By whose definition is a stressor always unpredictable? And what does that mean?

I have a speaking engagement next week. It has been scheduled for many weeks. I will prepare for it and practice, and I will still get sweaty palms and feel short of breath as I start speaking. Public speaking is a very predictable stressor for me. In my body, it is a challenge to homeostasis.

Yes, pregnancy is a very common experience across human history. But the notion that pregnancy is predictable—seems like a logical fallacy, to me. Isn’t it inherently unpredictable? What you say above is something that can be said at pretty much every step along the way: “It’s a part of pregnancy that is natural and normal and necessary, but it is complex and it can go wrong.”

There’s a clear average trajectory of development across pregnancy. But, despite the way we talk about this process in pregnancy books, tracking apps and medical literature, there is no one standardized way in which that development progresses. There are variations in every single individual, shaped by all of the factors on the maternal stress map, and by genetics—the fact that our bodies are different, the bodies we are growing are different. Even in the same individual, that trajectory can look remarkably different from pregnancy to pregnancy.

And, importantly, at the end of that trajectory, we don’t end up in the same place that we started. We don’t return to previous set points. We are learning, more and more, about how our physiology is changed by pregnancy, for the long term. So many systems that are considered part of the self-regulating processes of homeostasis are altered by reproduction: reproductive hormone cycling, immune response, cardiac function, metabolic function, dopamine and serotonin responses. Reproductive history shapes our long-term health, through gains and costs.

MOLLY: Ok, I think unpredictable might be the wrong word here. I stand by predictable, though (more on that soon). I should have used the word reactive.

Your body is reacting to a stressor that is public speaking (this is a stressor for you. This is not a stressor for every human on earth….lucky bastards). It may seem predictable because it has been on your calendar for months, but it is not something that the human body has adapted to respond to as it has for common everyday things (like eating or waking up). You are reacting to an event. A single event. A moment in time. It is your perception of that event occurring at any specific moment when you let the concept of the event cross into your brain as a stressor. And your physical response is reactive at that moment.

As you point out, physiological changes during pregnancy cruise along a general trajectory. Things go up, things go down, things compensate for that up and down. The up and down is what supports the development and birth of the new human. I fully agree that casting the expectation that we will all fit the “average” of this trajectory as represented in apps and pregnancy books is bullshit. However, I think the bullshit nature of those information sources is more related to expanding the range of what is “normal” vs. throwing out the trajectory altogether.

Back to our old friend, cortisol. If cortisol did not increase, the pregnancy would fail. It is a predictable and important increase. As are all the changes for the mediators and carrier proteins and receptors that regulate cortisol. Will some women naturally have higher or lower cortisol than the average? Absolutely. Will that higher or lower concentration be problematic for them? Potentially. But it doesn’t mean that pregnancy is a stressor. Pregnancy is a physiologically challenging event that uses cortisol in a new, crazy way.

Yes, things go wrong during pregnancy because this is not a perfect system—evolution does not require everyone to survive, just most. Which is where we got that statement, “It’s a part of pregnancy that is natural and normal and necessary, but it is complex and it can go wrong.” Those things may feel unpredictable to us at the moment, but are they really? You make big changes to the cardiovascular system, you change the risk of cardiovascular disease. As for long-term changes, pregnancy is its own physiological state and its own physiological challenge that may reset our baseline, as you point out. But that doesn’t mean it resets the baseline because it over stimulates the stress response pathways.

I wonder if we’re approaching this on two different levels? Different timescales— adaptive traits vs individual experience? Or is it that I am starting in the brain and you are starting in the body?

I am defining a stressor as an external psychological stimuli that triggers the stress response pathways. Starting in the brain.

My use of predictable and unpredictable reactive relates to how we, as humans, have adapted to spread our genes.

I’m not an evolutionary biologist but I do think semantics around stress, especially, are important here. If we separate the internal changes during pregnancy from the external stressors, you can eliminate risk factors that layer on weight to an already complicated, physiologically challenged system. We can view the wonder of a healthy pregnancy that requires no medical intervention while honoring the potential risks that will absolutely require medical intervention. And then we can address why external stressors should be limited or eliminated, as possible, without having pregnancy, itself, within that category.

CHELSEA: We agree that the semantics matter! One thing I came to appreciate while writing Mother Brain was the degree to which science requires categorization, but the human body rarely adheres to clearly defined categories.

Brain vs. body: They’re not actually separate things. Stress response pathways are not self-contained. They exchange input with all the other systems I mentioned in my previous note as being changed by pregnancy.

Predictable vs. reactive: By your definition, wouldn’t the stress of poverty be predictable, too? Deprive someone of their basic needs and, predictably, you raise the risk of disease and other harmful effects.

External vs. internal: That’s a very porous line, especially when you are talking about pregnancy. Our bodies are not actually separate from our environments. External stressors become internal ones. The work around adverse childhood experiences makes this really clear. The nature and number of significant stressors a person faces in childhood can shape their health much later in life, even decades after those stressors are no longer present.

My biggest worry here is that framing a healthy pregnancy as one not requiring of medical intervention, as pure or separate from external stressors and not resulting in negative health impacts, will do the opposite of what I know the Maternal Stress Project is aiming at, which is to shift the burden of alleviating stressors from the individual to society. Then, a pregnancy that is complicated in any way or that does result in any negative health effect is an “unhealthy” one that the pregnant person has allowed to be tainted by the outside world. (I know you don’t see it that way, but I worry about how it feeds the cultural script.)

One more point: Pregnancy costs us, no matter whether it’s a complicated one or not. We gain a ton, including some real physical and cognitive benefits. But there are, undeniably, costs. We do not return to baseline. You can see it in Liisa Galea’s work. And you can see it in the research on people who have lots of kids. Grand multiparity, or having five or more kids, is linked to higher rates of dementia, heart disease, diabetes, and more. In areas without good perinatal care, it can significantly increase adverse maternal outcomes.

Bruce McEwen has written about cumulative allostatic load as “the cost of adaptation.” I think there is a cost of adaptation to pregnancy—it is a stressor—and recognizing that cost as real and present in every single pregnancy is a key to advocating for quality care for all.

MOLLY: Ok, busting out Bruce McEwen citations. Well played, Chelsea!

I have been trying to avoid getting into the weeds of the Reactive Scope Model, but it might be unavoidable at this point. It is the model that I wrote with Michael Romero and Nicole Cyr in 2009 as a way to settle on language around stress, homeostasis, and allostasis. We adapted it for pregnancy in this paper, and that is what I danced around for the second “Centering pregnancy…” post.

Funny enough, McEwen and Wingfield (authors of the allostasis model) wrote a response to our first Reactive Scope Model paper to make the case that we are pretty much all saying the same thing but each model has strengths and weaknesses. Revisiting that paper, I noticed that McEwen and Wingfield also use the language predictable and unpredictable. And, they bring up lactation as an example of a homeostatic challenge. Here is how they write it:

“[A] cow that begins lactation undergoes morphological, physiological and behavioral changes so it can raise a calf. None of this is essential for the maintenance of homeostasis of the cow, although homeostatic set points will have changed from pre-lactation levels…. the process of preparing for lactation involves regulation of gene expression. Furthermore, termination of lactation involves turning off of many genes involved. Of course the cow lactating must do so to reproduce successfully. But the adjustments in homeostasis that occur during these life cycle events are to accommodate changed physiology as part of the predictable life cycle, not simply responses to deviations from some set point that maintains life processes.”

They also use unpredictable in the context of stress:

“Superimposed on this predictable life cycle are unpredictable events, including many potential stressors, requiring immediate physiological and behavioral adjustments to cope.”

I would actually argue that poverty is not a predictable event. The stress of poverty is associated with the body’s response to the massive unpredictability of poverty—the financial instability, the food insecurity, the housing insecurity, and everything in between.

Back to pregnancy, even McEwen would describe pregnancy as a life cycle event. A predictable life cycle event. But even a predictable life cycle event can do damage to the body, as you point out.

At some point I randomly texted you: “Chinook salmon!”

Followed by the explanation:

[Chinook salmon] literally DIE from the homeostatic challenge related to spawning. BUT no researcher who studies Chinook salmon would call spawning a “stressor.” Spawning is a predictable, adaptive homeostatic challenge.

It is actually critical to separate external and internal stressors in the journey towards spawning from the physiological extreme related to spawning (that includes insanely high cortisol levels). It’s not a perfect analogy because… well… they usually die. BUT the important thing is that you need to limit the number of internal stressor (e.g. osmotic stressors from human-related salinization of rivers, climate change) and external stressors (e.g. predators, angler catch-and-release) in order to make sure *more* salmon get all the way to the end of spawning.

They are more vulnerable during this time. They are more likely to have their health (and mortality) impacted by stressors. But spawning, itself, is not a stressor.

Ok, salmon aside, I think what I’m trying to get to with pregnancy (and extrapolating to other points of physiological flux) is a starting point where we are not automatically pathologizing these stages of life. I don’t want these changes to automatically reflect something to fix (and that might relate to my feelings about being in a patriarchal system that loves to fix things that are wrong with the female body).

Maybe I am stuck on semantics for that reason.

I want a starting point that embraces the middle ground—the natural and the risky. A pregnancy that is complicated can be related to a body pushed over the edge because this predictable life cycle event is a physiological extreme. Or it can be related to successfully walking that tightrope but ultimately getting pushed off by stress. But we need to keep the two separate—pregnancy/postpartum physiology and stress response physiology—and in their own distinct categories if we are going to effectively peel apart the layers. We need to be able to see the stress layer on its own in order to discuss why mitigating, buffering, eliminating stressors is especially important during this phase of life as preventive care.

I definitely do not want the way I am currently describing all of this to result in the concern you express—“framing a healthy pregnancy as one not requiring of medical intervention, as pure or separate from external stressors and not resulting in negative health impacts… ”—so… work in progress?

On the topic of adaptation. For the stress field, adaptation is mostly used in the context of chronic stress. It’s how the body shifts as a cost of challenging the stress response system repeatedly or continuously. It's an overcompensation that sticks around.

You are absolutely right, Chelsea—“We gain a ton, including some real physical and cognitive benefits. But there are, undeniably, costs. We do not return to baseline.”

I’m stuck on this.

And I LOVE that you have me stuck on this.

Pregnancy does have lifetime benefits and costs (yes to the work out of Liisa Galea’s lab!). In many cases—morphologically, behaviorally, physiologically—we never return to baseline.

BUT those long-term changes are not because this life cycle event overloads the stress response system. Pregnancy has its own suite of morphological, physiological, and behavioral changes. It is its own unique experience for the human body. It has its own unique long-lasting changes. Some changes are related to the new role of parenting, of course (let’s put those aside) but some are more closely related to a scar—a side effect of pushing too far.

Maybe we can still use the term “adaptation”? I would still argue that we need to keep it separate from adaptation related to chronic stress (and adaptation as used in evolutionary biology). But I think the long-term risk (and benefits) that you bring up is completely relevant to everything here. Human pregnancy is understudied to begin with, opening this can of worms is a whole new… well… can of worms. And I’m here for it!

With all of this in mind, the long-term risk of pregnancy can be related to the lasting changes from pregnancy or the lasting changes from the stressors associated with the experiences of pregnancy. Again, we don’t have the research to prove out or separate the two but… hmmmm… it’s really interesting!

CHELSEA: I mean, if I’m going to debate the nature of stress with a stress physiologist, I better quote people who know a lot more than I do.

I keep writing and deleting things about allostasis and allostatic load and my understanding, limited as it is, of McEwen’s work1 . But I’m not sure it’s helpful here. The bottom line for me is, I just cannot see the separation of pregnancy physiology and stress physiology, still.

Pregnancy changes our stress response and its hormonal mediators. It alters the amount of energy we have available to cope with outside stressors. The trajectory of change during pregnancy is subject to—may be shaped by—the wear and tear our bodies have experienced before ever being pregnant. The degree of stress we experience during pregnancy, plus our body’s capacity for coping, affects the physiology of pregnancy. And, over the rest of our lives, the influence of our reproductive history—the gains and the costs—interacts with our stress response to shape long-term health.

So, is pregnancy technically a stressor? Does it matter?

I get the fear of a patriarchal system that likes to “fix” things that are wrong with the female body—really. But the idea of a perfect pregnancy is a tool of the patriarchy, too. And the way to fight that is to point to the physiological extremes that make every pregnancy precarious and that require real support. You’re really good at that.

When we started this conversation, I asked a few friends and family members—also mothers—what they think when they hear the sentence, “Pregnancy itself is not a stressor.” I didn’t offer any other context.

The response that stands out: “That is a bald-faced lie.”

What you are doing here is so important, and I want readers to see themselves in it.

MOLLY: I want readers to see themselves in it too. I absolutely hear you and appreciate this point. Honestly, it's a bit of a dagger hearing that I might be missing this.

How about this: Pregnancy is stressful, but pregnancy, itself, is not a stressor. The stressors related to pregnancy are identified in the overall map as nodes and connections, but pregnancy, as an independent stressor node, is not. So, to your questions:

Is pregnancy technically a stressor? NO.

Does it matter? YES.

I still feel that miscategorizing pregnancy as a stressor is problematic. Pregnancy is superhuman. It is the most amazing feat the human body will ever go through. I worry that as soon as we pathologize it (and, unfortunately, “stress” still carries a negative connotation in relation to health), we lose sight of the incredible-ness that is this superhuman feat.

I want to start from a place that says, “You are a fucking superhero.” Even superheroes meet their match (pushing the body too far) every now and then. Even superheroes get thrown an unexpected chunk of kryptonite (stressors) every now and then. Even superheroes face a foe with a hand tied behind their back (genetics, early life stress, weathering) every now and then. Or encounter all of the above. Even superheroes can be broken.

The fact that your body is working around the intense physiological changes of pregnancy makes you a fucking superhero. Period. Complications classified as “unhealthy” are never your fault. They are never a failure of your body.

Stress is an additional layer. We have to keep the layers separate.

A stressor, by the definition I am using, is any stimuli that causes an acute stress response. The acute stress response is quick. It is a fire (stressor) that sets off a fire alarm and the team to fight the fire (stress response)—it triggers, sends in a response team, responds to the fire, cleans up the mess.

A sustained stress response or a series of stress responses are what become detrimental to the body. Only so many times you can respond to a fire before the home becomes unlivable. That is chronic stress.

Pregnancy physiology changes on a different time scale in response to the shift in needs—sustain a pregnancy, build a human, birth that human, care for that human. It isn’t a response, it is a full on shift in alllll the things. It doesn’t cause an acute response. It does not set off the fire alarm.

As you beautifully point out, there is a lot of overlap with the hormones and pathways and mediators that both pregnancy and the stress response affect. Evolution does not start from scratch—the human body recycles and reuses a lot of hormones and pathways and mediators for a lot of different roles.

Discussed earlier, cortisol in pregnancy is key for the elevated metabolic demands during pregnancy. The stress-induced cortisol response itself does change but that is equal parts a side effect of elevated cortisol and a protective measure; the changes do not match classic chronic stress effects on the cortisol response, they are opposite (decrease instead of increase… but I’ll save that rabbit hole for another day). With that said, it is interesting to think about the permanent shifts related to pregnancy-related changes (as discussed in the response prior about adaptation) but that still does not make me want to classify pregnancy as a stressor.

Stress is still a fire. The stress response is still a fire alarm.

Pregnancy is an increasingly complicated home—an apartment on the 50th floor, stuff piling up in the living room, furniture rearranged to block an entrance or exit. A home on the 50th floor with stuff piling up and an entrance or exit blocked is a risky arrangement to live in to begin with. Add in that those piles of stuff might be more flammable and in some cases, an earlier fire (life-time stress) might have left burn scars that make the home more prone to flare up.

A fire in that complicated home is harder to respond to, harder to put out, harder to clean up. It is riskier. It can leave more permanent damage.

The complicated home of pregnancy is inevitable and unavoidable (unless, of course, you don’t get pregnant to begin with). But, a fire is not inevitable and, in many cases, the fire is avoidable. It is not 100% avoidable in the context of birth and motherhood in America today, but that is why we’re doing this project.

And that is why we need to keep the layers of pregnancy and stress separate.

CHELSEA: The reason I had such a strong reaction to the statement, “Pregnancy is not a stressor,” is directly linked to something you just said. I am not a superhero. None of us are.

We are people living in the bodies we have, which have been shaped by all of our life experiences, good and bad. Very few of us get through life without some of what could be characterized as scars in the metaphor above. Many of us add more during pregnancy and the postpartum period. We are the sum of our lives.

I don’t want to pathologize pregnancy. I also don’t want to pathologize the state of being a human in the world. No one who deals with complications during the extreme experience of pregnancy should feel like a failed superhero. And I know that’s really not your aim either.

I don’t expect we’ll come to an agreement on the language. But that doesn’t change how I feel about the important work of making pregnancy go better for more people, which I know is the aim of The Maternal Stress Project.

MOLLY: Yes. And.

This perspective is so appreciated. The words themselves, and how we, personally, internalize them, also flavor our perception of stress and stressors. It is important to keep that in mind.

“We are the sum of our lives”—my biologist brain immediately went to telomeres. Telomere length, thought to be a measure of cellular aging, is affected by stress. But the data on whether pregnancy itself affects telomere length are messy.

Stepping back with your words and writing as a filter—the research investigating and describing biological mechanisms operates on averages and does a poor job of capturing the nuance of humans. “We are the sum of our lives”—you cannot separate the physiological load of pregnancy from the stressor load associated with pregnancy (and birth and caregiving). Maybe we need to take an approach that doesn’t pathologize “the state of being a human in the world” but recognizes that we have opportunities to make that world better and a bit less stressful?

Just as a fun thought experiment, we could swap out “pregnancy” for another moment of physiological flux, and state: Perimenopause is NOT a stressor… Then, we could start over from the beginning!

I won’t though. I think the conversation would go exactly the same. And I love that.

CHELSEA: Funny—a big topic of conversation with my 6-year-old this week has been speaking up when your friends do or say something you don’t agree with, and how real friends will respect you more for doing so. Thanks for this chance to put that idea in practice. I’m glad to be your friend.

MOLLY: This has been so valuable for me as a human (and the project, of course). I’m glad to be your friend too!

Leave a comment to join in the fun2!

The Maternal Stress Project is an educational and idea-spreading initiative and we want it to be available to all. You can subscribe for free and get all posts delivered right to your inbox. However, if you feel compelled to bump up to a paid subscription, your generous support will facilitate the growth of this project… and be much appreciated!

Sharing and spreading the word is equally valuable and appreciated!

Quick note from Molly to Chelsea: Allostasis is a slippery fish. The more you try to understand it, the less it makes sense. A “limited understanding” is a much better starting point than what I have cooking in my head around allostasis!

Quick note from Chelsea to Molly: Yes, I've gathered that, especially as one gets into the details. But what I find helpful about allostasis is that it incorporates both external stressors and life cycle events, in an energy supply-and-demand model that feels true to real life. In the response you link to above, McEwen and Wingfield specifically call reproduction an “anticipatory” life cycle event that adds to “allostatic load.”

Quick note from Molly to Chelsea: Reflecting back, I do think seeing the entire body from an allostatic load perspective (regardless of where that load is loading) is incredibly valuable, and I see why this aligns with your statement that "we are the sum of our lives." I'm coming around to this! (but I still would not call pregnancy a stressor 😅)

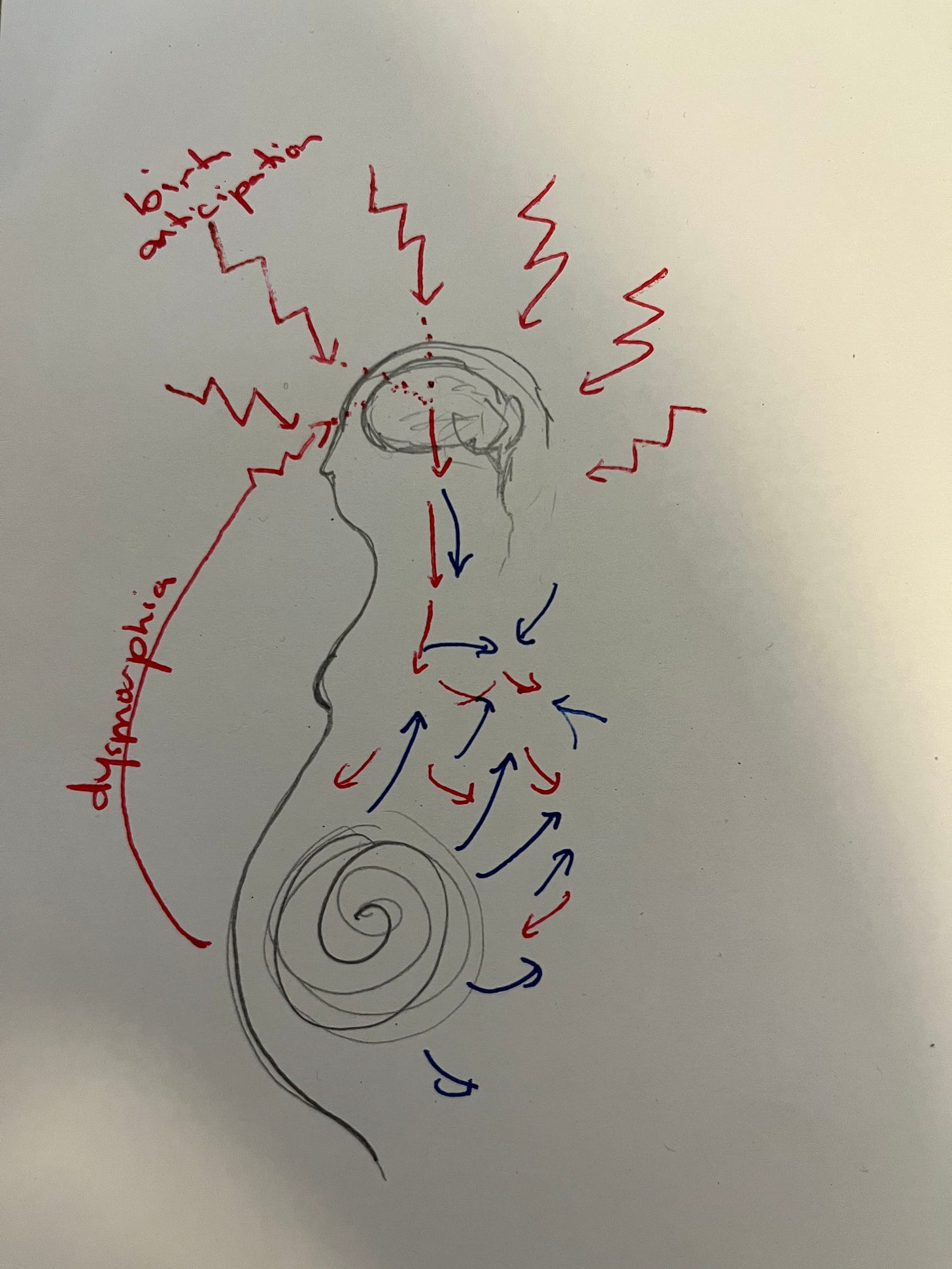

(Molly) I’m a visual learner and thinker so in response to the banter between Chelsea, Jensen and I in the comments, I drew up this little sketch to illustrate how I was thinking about internal changes versus external stimuli related to pregnancy. Blue = pregnancy changes. Red = stressors and stress response.

This was such an interesting read. Thank you !

I think one way to combine your two perspectives, is by thinking of the concept of biological interactions. There is a biological interaction between Pregnancy and acute stressors - in relation to health outcomes. Such that pregnancy itself changes your susceptibility to the stressors. The stressors themselves might not cause adverse health outcomes by themselves, and pregnancy itself would not - but together they do. A biological interaction - when two factors are necessary. This way of defining causal relationship is well described by epidemiologist - Kenneth Rothman

Interactions is also just a way to acknowledge the complex biology of health and disease and that there may also be unknown causes that are part of the causal network of factors that ultimately led to the outcome.

Anyway. Much appreciated to read your discussion and love your project !

This was super interesting! I think it would’ve made a great podcast also.

I felt anxiety during pregnancy in anticipation of having a baby. I think I would have felt the same thing if I had been preparing to adopt. What about pregnancy as the state of expecting a baby to show up being a stressor?

(I struggle a bit to understand the definition of a stressor, so please excuse me if this is a silly thought!)