The ignored health risk of motherhood

Can we change the narrative of self sacrifice and maternal martyrdom?

“Our expectations of the ‘good mother’ have tended to expand right as women began to take up space formerly granted to men.” —

, The Good Mother Myth: Unlearning Our Bad Ideas About How to Be a Good Mom

“All I want is a healthy baby” – I never thought of that statement as dangerous until recently1.

It always seemed like a standard comment for those staring down the gauntlet of birth. A public acknowledgement of expected priorities as we approach the right of passage between pregnancy and everything after. Something a “good mother” would say2. A selfless mother. The mother who would willingly sacrifice anything and everything for her child. The mother who would lift the car to save her baby even if she pulled every muscle in her body and broke every bone.

See the problem?

Regardless of whether or not the exact statement actually escapes the lips of an individual mother or potential mother, the “I just want a healthy baby” narrative has embedded itself in all the ways we talk about priorities across the perinatal journey from fertility to birth to infant feeding.

Not a new issue, of course, but given the current political climate, I am starting to worry about how this problematic focal point might be further weaponized against women. How the simple statement might become even more dangerous.

The weaponization would come from the malicious tentacles of “isn’t this what you want?” – an excuse to double down on exerting what it means to be a mother in the scope of a certain political agenda. A tool for benevolent sexism. An excuse to increasingly ignore women’s health needs, provide zero support, and make it seem like self sacrifice was their idea all along.

While the rest of the writing below will focus on the perinatal journey, it is important to note that the “all I want is a healthy baby” narrative does not stop at pregnancy and childbirth. If women are expected to deprioritize their own humanity from the very minute they begin carrying a bunch of cells (that may or may not turn into a baby), do they even have a chance of dislodging the maternal martyrdom framework for every other aspect of parenthood?

Ok, let’s focus back in…

Did we ever really prioritize the mother?

In 2018, Dr. Allison Stuebe, professor of Maternal Fetal Medicine and co-Director of the Collaborative for Maternal and Infant Health at University of North Carolina School of Medicine, commented on the state of postpartum care in the U.S.:

"The baby is the candy; the mom is the wrapper. And once the candy is out of the wrapper, the wrapper is cast aside." – Dr. Alison Stuebe

The task force that Dr. Stuebe led, drafted new guidelines for ACOG with clear recommendations to step up postpartum care, noting how “[the postpartum period is] devoid of formal or informal maternal support." Since the publication of those guidelines, postpartum care started to make strides in the right direction in this country. It has been generally adopted to have a first postpartum appointment within three weeks after a normal birth, with any additional appointments as necessary3.

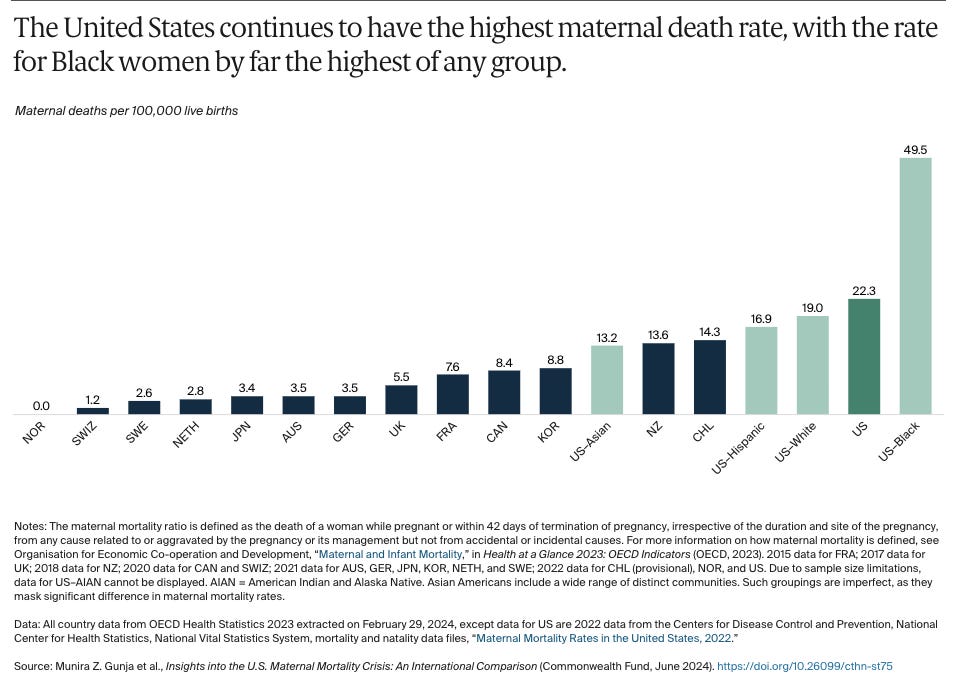

Some measures started improving but we still have a maternal health crisis in this country. The US ranks last for maternal mortality amongst high-income nations. Rates had started dropping in the last few years. Between 2022 and 2023, the U.S. maternal mortality rate dropped from 22.3 to 18.6 maternal deaths/100K live births. But these averaged statistics mask a key piece of this data set. Maternal mortality rates improved for every demographic except Black women. The maternal mortality rate for Black women increased to 50.3 deaths per 100K live births, a rate more than three times that for any other racial or ethnic group4.

We always had a long way to go to solve the systemic issues underlying the maternal health crisis, especially the Black maternal health crisis, but at least these crises were finally being openly discussed, researched, and funded. We were starting to see and treat mothers as more than a candy wrapper.

Fast forward to 2025 and things have taken a dark turn5.

Research on women’s health and health equity will likely stop or at least slow as funding gets stripped away. The increasingly aggressive attacks on body autonomy will affect individuals AND have the repercussions on maternal healthcare access, especially in regions that already had maternity care deserts. General misogyny flooding every system will continue to skew the way this country values women and their bodies. And then the real kicker – none of the factors that influence maternal health and maternal mortality rates will be reflected in the data because now THE DATA ARE NOT BEING COLLECTED.

Needless to say, I am feeling an urgency to hold the line and keep this course correction going in the right direction.

How do we do that? Well, I’m sticking with what we might actually have some control over these days – cultural narrative.

Back to that narrative…

Admittedly, maternal mortality is a dramatic statistic to kick off this discussion with. Yes, a mother’s survival should be a critical consideration but why should “yay, I lived!” be the baseline for a birth experience in 2025? Especially given how the current leading causes of maternal mortality actually happen outside of the hospital6.

Important to this discussion, that healthy baby + living mother baseline may only further cement the “all I want is a healthy baby” focal point as the positive outcome. Such a baseline masks the importance of the experience along the way and ignores other drivers of long-term maternal health: the emotional journey and stress load7.

Ok, I know what you may be thinking – Molly, you are clearly biased – and, yes, I always have my stress lens on, but hear me out…

Looking at ways of holding the line while facing a historical backslide, here is the bug in my brain: can we infiltrate the narrative and continue shifting the culture of risk analysis?

Can we change how we discuss prioritization? Can we ensure that maternal stress load carries proper weight in the mom and baby *risk : risk* equation? Can we elevate a calculation that truly weighs the risks to BOTH mom and baby for any given recommendation/procedure? Can we alter the way we discuss the goals along the journey to and through parenting? Can we go so far as centering the mother and prioritizing her experience and her needs when risk is acceptably low all around?

One of my goals with the Maternal Stress Project has always included finally FINALLY factoring maternal stress exposure into the risk : risk equation for mom and baby. I am not talking about “stress” in the question/answer “have you been under stress recently?” that comes with silly standard responses and always seem to blame the mother for any degree of fetal stress exposure. Rather, I am talking about how maternal stress exposure has become an acceptable risk in the over-prioritization of baby’s outcome and health. Especially when zero tolerance for any amount of risk on the baby side of the risk : risk equation requires ignoring the real risk of stress and psychological harm to the mother.

The risk : risk equation starts with higher maternal risk. Let’s recognize that.

The maternal body naturally puts itself at a higher risk by prioritizing the growth, development, birth, and care of the new tiny human. Physiologically, every system across the pregnant body is pushed to the absolute edge (and sometimes goes over):

Even if everything is humming along as evolution intended, the pregnant/postpartum body would still have a higher risk level than the risk level for the normally developing baby. The maternal body naturally protects and prioritizes the baby. Evolution does not require all individuals to survive, it actually works best when some are sacrificed along the way. “Natural” fetal prioritization can come at the cost; an elevated risk is a normal part of the process.

In addition, the path to parenthood can be incredibly stressful for anyone. The fertility journey, perinatal care access, birth, postpartum recovery, breastfeeding, every element of adjusting to life across that entire timeline (especially in a country that does not support new parents) is riddled with potential (often, inevitable) stressors.

The risk for the maternal body already teeters on the edge. Any additional stress could tip it over. However, healthcare and recommendations and cultural narratives seem to ignore this teetering by focusing around that zero risk tolerance for the baby.

Zero risk for life/death situations is understandable, of course. However, most situations are not so clear. There is usually a degree of grey zone. Decisions made in that grey zone could expose mothers to unnecessary levels of stress, elevating risk and impacting their health.

Again, such a risk has not been fully quantified, described, or linked to negative health outcomes because of where we stand with research gaps on the subject. While we do need to strengthen the evidence around maternal health risk, it’s important to note that we don’t seem to have the same hesitation when we encounter data gaps for baby prioritization. On the baby side of the equation, many decisions will skip right over data gaps in order to accept the zero risk standards8.

In addition, when we center zero risk to baby and accept the skewed ratio of elevated risk to the mother, we end up with sacrificial narratives that embed in the social conscience: e.g. c-sections are to “save the baby” even when that is not necessarily the case; breast is best actually reflecting that breast is best, for the baby even when data does not fully support the absolute superiority of one feeding method.

I am not saying c-sections or promoting breastfeeding is the wrong approach. I’m saying there is often grey zone on both sides, in terms of the risk to the mother and the risk to the baby. We tend to accept a range of outcomes in the grey zone for the maternal body while shutting the door to the grey zone for the baby. Baby risk, in most cases, becomes black and white, life or death, even when it isn’t.

I am not a healthcare provider and I know this is far more nuanced than I am making it seem. Perhaps the trickiest part comes down to how this new risk:risk analysis will require acknowledging impacts of short-term decisions on long-term maternal health outcomes. Outcomes that do not directly result from things going wrong during fertility → birth → postpartum care but could trace back to how the experience contributes to stress load and the impact of those stressors reverberating for years afterwards.

[Quick note: stress may be inevitable in those grey zone cases BUT support for, or acknowledgement of exposure, could go a long way to soften the impact of those stressors.]

This is an uphill climb and the hill just got a bit steeper. Changing standards of care often require extensive research, and, well, the longitudinal studies that could lend evidence to such a recommendation have yet to be done… or funded… or conceptualized… blah blah blah (you know this drill).

With that depressing timeline in mind, perhaps cultural narrative could be our short cut? My hope – planting this bug in someone else’s brain will keep the small shifts moving in the right direction.

Maybe that bug will slowly (very slowly) influence clinical care. More realistically, this is a reminder that the shift can start with anyone at any time. A narrative shift could relate to how we interact with friends, family, community members along their journey. It could include acknowledging the stress, celebrating the joy, and supporting the mother without judgement. A narrative shift could include emphasizing the importance of birth outcomes AND birth experience. It could show up in a response when a friend goes against cultural script, or how we ensure every hope/wish/goal for the journey to and through pregnancy and birth and early parenting is met with support, with no room for shame9.

The more we work against the grain to no longer accept maternal stress as an inevitable requirement for “saving” a baby/child, the more we can hold the line and resist the backslide.

We do not need to become candy wrappers again.

Coming up!

I have been working with a few brilliant brains to explore a better risk : risk analysis – how it shows up in different stages of the early parenting journey and where the opportunities are for narrative shifts that incorporate maternal stress. Specifically, conversations focusing on the reality, the risks, and the solutions related to breastfeeding and sleep protection (with

), C-section rates and birth trauma (with author ), and the NICU experience (with Dr. Kobi Ajayi).Stay tuned!

Thanks to a great discussion with

and her excellent book, Invisible Labor: The Untold Story of the Cesarean Section. More on that discussion soon!I love how

reframes the research in what has come to define what it means to be a ‘good mother’. Also, not sure if this was a specific directive on the cover art, but I love that it has the child centered and the mother’s head slightly cutoff. Intentional, Nancy?

If you had your first baby in the last 5 years or so (or live outside of the US), you might be thinking — “wait, what?!”.

It seems a bit ridiculous upon reflection that when I had my babies (last one was just over nine years ago), having your first post-birth appointment at 6 weeks postpartum was pretty standard. Everyone (well, at least my friends) called it the “everything looks ok down there!” appointment to get clearance for exercise and sex.

(and now, even that description seems like a perfect example to demonstrate who that 6 week appointment was actually for 🤔)

Other more brilliant minds have written about and discussed the causes underlying these statistics, how the Black maternal health crisis shows up, the reasons the crisis disproportionately affects Black women, and the innovative ways to change the trajectory. In the context of stress, I discussed this with Dr. Karen Sheffield Abdullah last March:

Ugh, I know. I keep doing posts like this. I am so sorry. I have tried to avoid writing about current affairs in this country but the shit just KEEPS COMING.

We often think about maternal mortality in terms of what happens in the hospital before/during/after birth -- sepsis, hemorrhage, eclampsia, etc. -- but the with more data finally being captured on the full spectrum of, a new study found that the number one cause of maternal death is suicide and homicide.

This quote from

, in her discussion with for Human/Mother about her birth experience, captures it so well:“Part of what made the birth of my second child so traumatic is the way I felt, which was so unbelievably invisible and disrespected. A birth that requires interventions isn’t necessarily traumatic (and one that doesn’t, can be). It’s all about the mother’s experience.” —

Oh boy, where to begin. Here’s an example - the nearly zero tolerance for risk related to vaginal breach delivery. One study, ONE STUDY, done in the late ‘90s captured data with two infant deaths following vaginal breach delivery vs zero infant deaths for c-section (out of …). After that one study published, not only was vaginal breach delivery halted at nearly every hospital BUT medical schools stopped training OBs to perform vaginal breach delivery. C-section became standard. Technically, today, you could have a vaginal breach delivery BUT you would need an OB who is trained to do the procedure. See the problem?

Electronic fetal monitoring is another good example of grey zone with zero tolerance. Get into the weeds on both examples with the excellent reporting by

in Invisible Labor: The Untold Story of the Cesarean Section.Important to acknowledge: even the "healthy child" part of the statement can be problematic. Parents of children with developmental or chronic conditions should not be made to feel less than either.

Thanks for the shout-out Molly. And ditto Nancy, I'm a fan of your work too, and it's so meaningful to have our books part of the same conversation!

This piece made me think about how important it is to look at the connections between zero acceptable risk to the baby --> fetal personhood laws ---> restrictions on abortion is super important. Doing so shows that in yet another way how constraints on bodily autonomy in one area of reproductive care (ie, abortion) also show up in other areas (ie, mothers who want to see their pregnancies to term, but want to balance risk to the baby with risk to themselves).

The first line of this piece stopped me dead in my reading tracks…I gave birth on March 10 and the nurse in L&D triage asked me what my main goal was for my delivery as part of the registration questionnaire she had to run through. The question stumped me partly because I’d never had to answer registration questions before as I have precipitous births and I barely make it to the hospital to begin with, but also because I was in the middle of contractions and I’d never really given Much thought to the question. My initial response was that I wanted to have an easy, smooth, natural, unmedicated delivery. But then a second later I (subconsciously) realized I’d said the wrong thing and amended my answer to “I just want a healthy baby”. Until reading this, I didn’t realize what I had just done. I started by giving my wishes for me. Then, after the nurse kind of looked at me funny, I realized that’s not the “right” answer. Crazy how culturally ingrained this is.