“This can be solved with relative ease”

Discussing eviction, child care, and maternal health with Julia Craven

The calendar flips to June tomorrow. School is winding down. Summer is here.

For those of us with school-aged kids, our schedule is about to flip too. Parents will navigate the irregular routine of drop offs and pickups that change every single week because we’ve put together some insane puzzle-work of day camps. Camps that we’ve strategically mapped out to do the double duty of keeping our kids happy and filling the no-school gap of summer child care.

And while most of us will battle some degree of stress and return at the end of the day to a home stinky from muddy shoes and sweaty clothes and mildewed towels that just never freaking get clean after a week of camp, other parents will come home to a different level of stress: an eviction notice.

Summertime is a hotbed of child care stress. Especially for those teetering on the edge already.

Last December, Julia Craven published a report for New America’s Better Life Lab that detailed the association between housing, eviction, race, and maternal health. In that report, she makes an observation based on the available data that perfectly characterizes the connection between the stressors of child care issues, housing insecurity, and racism in America: evictions increase for Black mothers with young children at the start of summer. And while Julia is quick to point out that the exact causality has yet to be proven, the correlation is so glaring that it is hard to ignore the intersection of these issues.

Housing is a known social determinant of health, to the degree that some have likened the solution — stable housing — to a vaccine. The ties relate to physical stress – e.g. not having a roof over your head, not having access to a climate controlled environment, links to food insecurity, exposure to environmental toxins – and psychological stress1 – e.g. instability, exposure to crime, financial strain.

In one study, mothers exposed to three forms of housing instability – falling behind on rent, frequent moves, homelessness – showed poorer health and an increase in depressive symptoms in each of the three scenarios. Another study demonstrated that maternal depressive symptoms that follow an eviction can last for years.

Most importantly, this problem, and its health impacts, disproportionately affects Black mothers, who are already at the highest risk for negative maternal health outcomes and experience the highest rates of maternal mortality.

As Julia points out in her report:

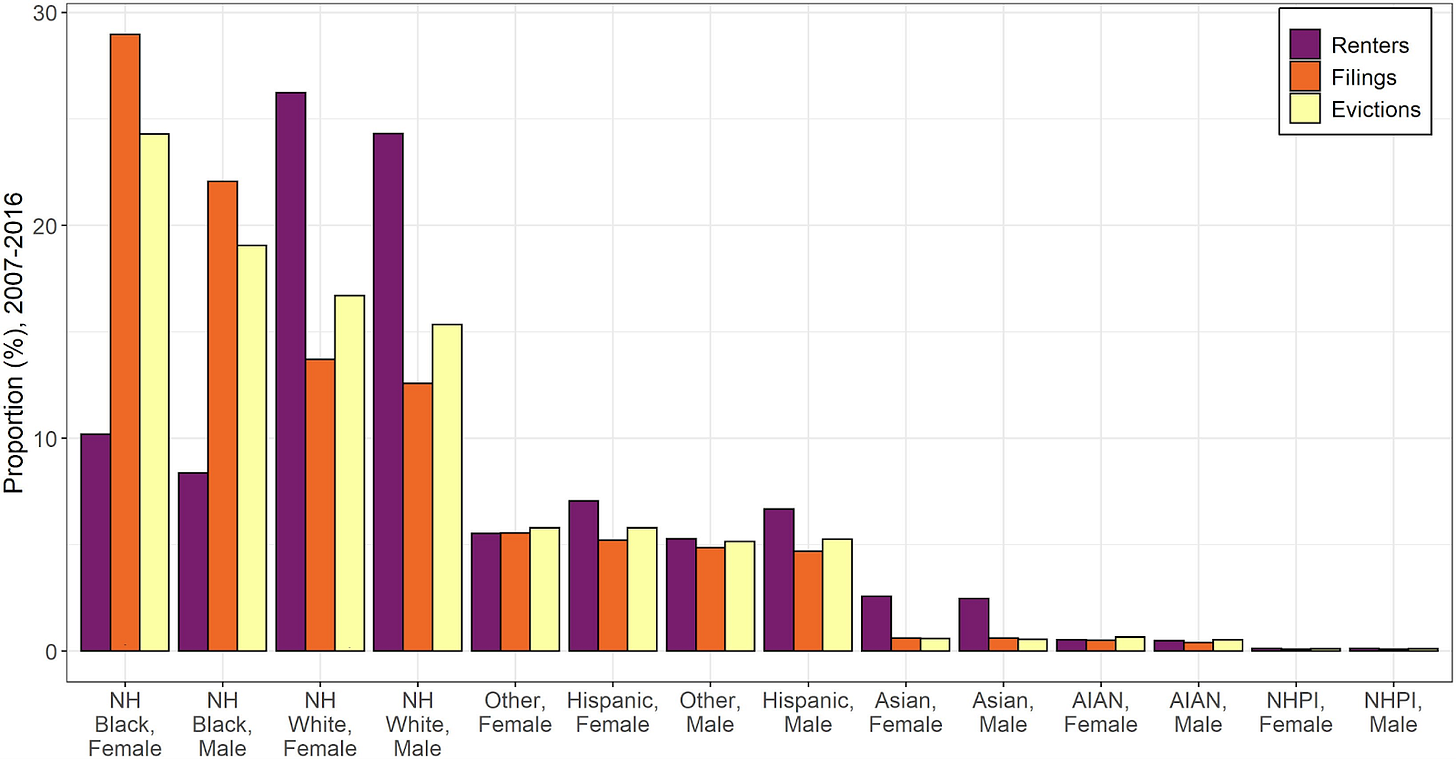

“Black renters comprise 18.6 percent of America’s renter population, yet they make up 51.1 percent of those affected by an eviction filing and 43.4 percent of those evicted nationally. Within this demographic, Black women with children are the most vulnerable, comprising 28.3 percent of the average annual rate for eviction filings and 12 percent of those evicted via court order—the highest of any other group.”

In addition to her work with New America, Julia also has an excellent Substack, Salt + Yams , where she explores everything from her own wellness journey to issues related to Black maternal health. She has written one of my favorite descriptions of where the reality of stress in our world meets the “solutions” that the wellness industry offers:

“Complicated systemic issues provoke people to seek out the snake oil salesman because taking his potion feels easier than contending with our country’s lack of universal paid leave, guaranteed basic income, guaranteed housing, and child care to help keep the most vulnerable among us afloat... The machine of capitalism is promising a cure for the problems it has caused. But we don’t need fancy supplements; we need access to nutritious foods. People don’t need another self-help book; they need child care. And, most importantly, we don’t need advice from the multi-billion dollar wellness industry; we need an overhaul of the systems that prevent us from being able to take proper care of ourselves.”

Julia’s views on how all of the stressors tie together and, most importantly, where the real, tangible, actionable solutions lie, are invaluable.

Diving into some of her brilliant work…

MOLLY

When did you become interested in Black maternal health, as a journalist?

JULIA

In 2016, I quit smoking. And I quit smoking after my Nana told me that my granddaddy, who was a former smoker, had died of lung cancer. She told me that and then mentioned the fact that I smoked. We moved on but I caught what she was saying. I went outside and I smoked my last cigarette.

That started me on my personal health journey. [At the time] I wasn't moving my body in a thoughtful way, I was having a lot of breathing problems from smoking, and I acted like I hadn’t been raised to know what a vegetable is. That kind of started this whole shift in me taking care of myself.

That's what pivoted me into maternal health – just this fear of dying and wrestling with whether or not I wanted to have children.

Eventually that became a topic of journalistic interest for me because I became fascinated once I started looking more into health and data – there were a lot of stories there. Somewhere along that road, as I got older, I started thinking about children, and if I actually wanted to have children. I knew that my mother, my Nana, and my great grandmother had all almost died giving birth. And that terrified me.

That's what pivoted me into maternal health – just this fear of dying and wrestling with whether or not I wanted to have children because of the maternal health outcomes for Black women in America.

MOLLY

I appreciate you sharing that perspective – calling out the additional stress of just considering parenthood with pregnancy as a potentially life threatening event to get there. That is something that is not talked about enough, generally, and yet it seems to come up in most conversations when I speak with Black women specifically. It’s so important to factor in that there is already added weight even before starting a fertility journey and pregnancy journey.

How did you decide to center around housing for the report and the work that you're doing on that topic?

JULIA

I had been thinking about housing too. It's one of the social determinants of health. I know people who have experienced evictions.

So when I started looking into what type of work I wanted to do at New America, I decided that I wanted to explore evictions. I wanted to explore how it specifically affects Black women.

It just so quickly became many 1000s of words. It is fucking ridiculous. But it's very reflective of the complexity of the issue.

And then the Future of Land and Housing, another program at New America came to us, and [brought up] that the Eviction Lab had just published a groundbreaking report with all this data showing that the group most affected are children.

They asked us: “would y'all want to be involved in interviewing them and figuring out some way to work together and see what can come out of it”. So we started doing that. And from there, it was clear that children are the most affected demographic, but it appears that it's mainly Black children. Then when I dug a little bit deeper. It’s Black children [who are most at risk for eviction] because the most marginalized group, in terms of leaseholders, is Black women with children.

What started as a blog post became a briefing, then a white paper, and then it just blossomed into this unofficial, mini policy report. It was not intended to be that. It just so quickly became many 1000s of words. It is fucking ridiculous. But it's very reflective of the complexity of the issue.

MOLLY

I so appreciate that. It's one of those things where you follow the thread and, when the thread is still attached to another point, you just want to keep pulling. In your report, it felt very much like that. There’s so much more to it. It's so interconnected. It's such an important issue. It goes so deep and you just keep pulling the thread.

When I was reading your report, and thinking through how you illustrate the issues of eviction and housing instability, it is such a clear example of how issues are connected as stressors

Considering housing and housing insecurity in the context of the graph in your report – how eviction rates are highest for Black women with children – it feels like an example of quantifying the relative intensity of this as a stressor across groups, especially when viewed through the lens of the experience of Black women in America.

How do you see this data? And what else do these eviction rates reflect?

JULIA

Particularly about eviction, and from our findings, child care is definitely one of the things that we believe affects eviction rates. Just because of how much coincidence there is between eviction rates, child care costs, and when people are more likely to be evicted – for example, people are more likely to be evicted during the summer which just happens to be the time when kids are not in school.

So again, while we don't have proof of that, there was enough correlation for me and my team to be like, “yeah, we're just gonna we're gonna write it, we have enough.”

Child care is definitely one of the things that we believe affects eviction rates.

It’s very maddening to me. It upsets me. It's frustrating. To just see this happen to people.

I'm someone who believes that being healthy, being in good health, being able to access well-being is a human right. That means that housing is a human right. That means that being able to give birth without an increased chance of dying is a human right.

[The current state] is just so disheartening.

MOLLY

The other thing that I was thinking about while reading your report was how this is a clear example of solutions that can have significant and immediate impacts on the health of mothers and children.

You outlined how these issues all feed into this problem and so there are multiple opportunities to alleviate the pressure and the impact – you can approach this specific stressor from the lens of housing, or the lens of child care, or the lens of guaranteed basic income, as solutions.

JULIA

Yes, this can be solved with relative ease.

It's certainly not something that this country cannot afford. There is money to allocate to this, but that money just goes towards other things that are considered more important by the people who make policy. So part of this is shifting the perspective around what actually matters.

We can do this. We can just not evict people.

One thing that I emphasize is that poverty + eviction in this country is cruel and unnecessary. And that's just a fact. It is cruel, and it is unnecessary. It does not have to be this way. We saw in the early years of the pandemic that things do not have to be like this. 10 million renters were able to stay housed because of emergency assistance programs.

We can do this. We can just not evict people.

MOLLY

In your report, you make really important ties to health, especially child health. In addition to data on preterm birth and pregnancy complications, what else have you seen as this relates to maternal health?

JULIA

A lot of the research is actually about kids. I was kind of shocked to see that there is pre-existing research about the effects, the health consequences of eviction and how it can affect a child and a parents’ mental health, their future financial health, and more.

Poverty + eviction in this country is cruel and unnecessary. And that's just a fact.

That research does exist and [yet we still haven’t fixed this problem].

MOLLY

One of the other things I realized, that I didn’t originally have connected on the stressor map, was the connection between housing and the judicial system. And this was something that you point out in your report, and that then connects to a lot of the other pieces related to motherhood and stress.

Is there anything else on the stressor map that you feel have strong connections in this context? Or something that needs to be more considered as connected stressors?

JULIA

Well, certainly financial stability. Also, the workplace. Social narrative sticks out for me too.

When a parent is evicted – when they are stressed about the eviction, when they are understandably focused on trying to find housing for them and their family – they can be “distracted at work”. And that [assumption] can lead to them getting fired or laid off.

Policies aren't human-centric. It's just “well, you're not doing your work. You're not performing. You have to go” versus assessing why this person is currently having trouble at work and extending them a bit more compassion and understanding.

That can also lead to them to forgo important medical care, to pay for climate appropriate clothing, etc. So it definitely does have a strong workplace connection.

As far as policy in the workplace, that's one of those things where policies aren't human-centric. It's just “well, you're not doing your work. You're not performing. You have to go” versus assessing why this person is currently having trouble at work and extending them a bit more compassion and understanding.

MOLLY

So this sits in the space where solutions exist on a community or interpersonal level alongside the broader policy level.

Thinking through solutions, where do you see solutions that are the most approachable and/or are the most likely to have significant impacts in this space?

JULIA

I'll tell you which one I think is most likely – one could be instituted starting on Monday – and which ones I would be most excited to see as a first step.

Ones that are immediately actionable include: robust funding of emergency rental assistance programs and eviction diversion programs. A diversion program that works really well will take a minute to set up and have it running properly. But, as far as the government giving money to people, we can do that. We can do that relatively easily. We can also enforce a moratorium on evictions until assistance and eviction diversion programs get back up and running. So those are the two that I believe are the most actionable.

I would like to see: universal care infrastructure, universal paid leave + medical leave, and after school and summer school programs for kids. Those last two, specifically, because we see a lot of evictions go up during the summer, and while we don't have proof of that as a cause of evictions, it's a correlation that is concerning.

The ones that I would most like to see would certainly be a universal care infrastructure. I would want to see universal child care for children zero to five. That's the demographic that is disproportionately affected by eviction, and the child care costs for that demographic are insane.

And not everyone realizes that. I was interviewed this morning, and I gave a number and said, “that's per child.” And the host was shocked by that. I had to explain that if you're at 19% of your income with one kid, and you have another one, you're hitting around 40% of your income. And the host was like “what the fuck?”. I had to emphasize “yeah, it's terrifying.”

We see a lot of evictions go up during the summer, and while we don't have proof of [lack of child care] as a cause of evictions, it's a correlation that is concerning.

So, I would like to see: universal care infrastructure, universal paid leave + medical leave, after school and summer school programs for kids. Those last two, specifically, because we see a lot of evictions go up during the summer, and while we don't have proof of that as a cause of evictions, it's a correlation that is concerning.

Part of that care infrastructure, to me, would also be guaranteed basic income, which is a little bit different from universal basic income because GDI is based on equity. It’s not just like everybody gets $1,200 like universal basic income. I’m making these numbers up for the sake of making my point, but it's more like your family makes $150,000 a year you get $500. This family that’s making $25,000 a year, they get $4,000 because they need that $4,000 to be above the income floor and you don’t.

MOLLY

Yup, it all ties together! Care infrastructure solutions impact so many aspects of life and yet, we're still fighting for what should be the most basic necessity.

Personally, I’m prone to optimism, for better or worse, and I have a “this is such a no brainer!” approach when looking at the data and putting the pieces together. I'm guessing you do, too? That feeling of “Here you go. Data. Backing up such a simple solution. Go do it!”. And then to experience pushback when it seems so clearly connected is so frustrating. The optimist in me always expects a different result.

Then again, I guess making the healthcare argument means you also have to get people on board to value women’s health…. but that’s another battle.

JULIA

What I did notice when I shared the report on Twitter (and maybe I should have I expected this because it's Twitter) was that, while most people agree that people should be housed, I got pushback along the lines of: “Well, where are these fathers?”; “why aren't they working hard enough?”; “They’re lazy”; “Why aren't they earning higher wages?”

I think that reaction is for a couple of reasons. One is that there's a really pervasive narrative about poor people in this country that we have to push back against with facts and human-centric storytelling. And the other, that I have noticed, is this belief that certain things can't happen to you.

I think it's very human to believe that “that thing wouldn't happen to me.” But if we set aside the ego for a second and be fucking for real, it could happen to you, very easily. For a lot of reasons beyond many people's control, we don't have a real sense of where we fall within socioeconomic classes. So a lot of people who think that they're middle class and that this could not happen to them are actually a part of the working poor. They're doing well… right now. They're maintaining things… right now. However, that may not always be the case.

There's a really pervasive narrative about poor people in this country that we have to push back against with facts and human-centric storytelling… One of them is, of course, these pervasive narratives about poor people. And the other that I have noticed is this belief that certain things can't happen to you.

So many of us are one missed paycheck, one healthcare crisis, one child care crisis away from being up for eviction. This is a very salient issue. I'm truly very happy that the people who were regurgitating these beliefs are currently able to pay their rent. But I implore people to step back and ask yourself if you missed one of your paychecks, would you be able to stay in your home? And for a lot of people the answer is “no”.

So that is something that I think about – how can we mitigate that belief that this can't happen to someone who did all the right things? We talk to people who have experienced eviction, and a lot of those people also “did all the right things”.

MOLLY

On the issue of narrative shift, one narrative around motherhood that I’ve seen come up, especially as it relates to federal funding for child care, focuses on the concept of choice, as in “well, you chose to have children so you should pay for your children / I should not have to pay for your children”.

Besides “choice” not really being a true choice for a good chunk of our country right now, the narrative layer you bring up also emphasizes the depth of the problem and the uphill climb for cultural change in this country.

JULIA

It’s a lot. And that level of hubris is so deeply American. Exceptionalism and individualism have taken a toll on our empathy and compassion for one another.

People get so caught up in the bootstrapping that they fail to see that our systems are failing us.

And these are the beliefs that you are made to believe. It's really unfortunate. I believe that with issues like evictions and child care and universal care infrastructures, people get so caught up in the bootstrapping that they fail to see that our systems are failing us. It shouldn't be a controversial statement for me to say that everyone deserves housing. People say: “Oh, you just want to give people a house to live in.” I’m here saying, “yes, I do.”

I’m not saying everyone should live in a penthouse apartment but I do believe that everyone should have safe, adequate housing. And everyone should have child care access. So, yes, I believe that.

MOLLY

As you said, it shouldn't be a controversial statement. It shouldn't be a problem to say that out loud.

JULIA

I don't feel like these are radical or hot topics. It's just compassion for your fellow human. That’s really what it is.

MOLLY

So another broad solution is breaking free of individualism and just have some empathy.

JULIA

Yeah, that’s a big part of it.

The Maternal Stress Project is an educational and idea-spreading initiative and is available to all — subscribe for free and get all posts delivered right to your inbox. If you feel compelled to bump up to a paid subscription (or pass one along to a friend!), your generous support will facilitate the growth of this project… and be much appreciated!

Sharing and spreading the word is equally valuable and appreciated!

When I started digging around for studies quantifying the psychological stress toll of housing instability and eviction, I ran up against research that tends to take the same troubling approach as I have discussed previously in the context of breastfeeding research – measuring maternal/parental stress because it impacts child health/wellbeing rather than describing the sources and solutions for maternal/parental stress.

The problem with this, of course, is not just the lopsided nature. The problem is that it does not frame solutions as a path towards reducing maternal stress but rather calls out maternal stress as a risk factor for children. Case in point, this quote: “housing insecurity may induce stress on the family and may thereby increase parents’ propensity to maltreat their children.” 🤔

You’ll notice that summary skips a few steps. Little expansion around assessing how the stress and stress-related health issues affect parents (especially mothers).

Thank you so much Molly for sharing this very insightful conversation with Julia. I am fascinated by her work and this link between the costs of childcare (esp in the summer) with evictions. We have made the decision in the past not to evict people and we can make that decision again.