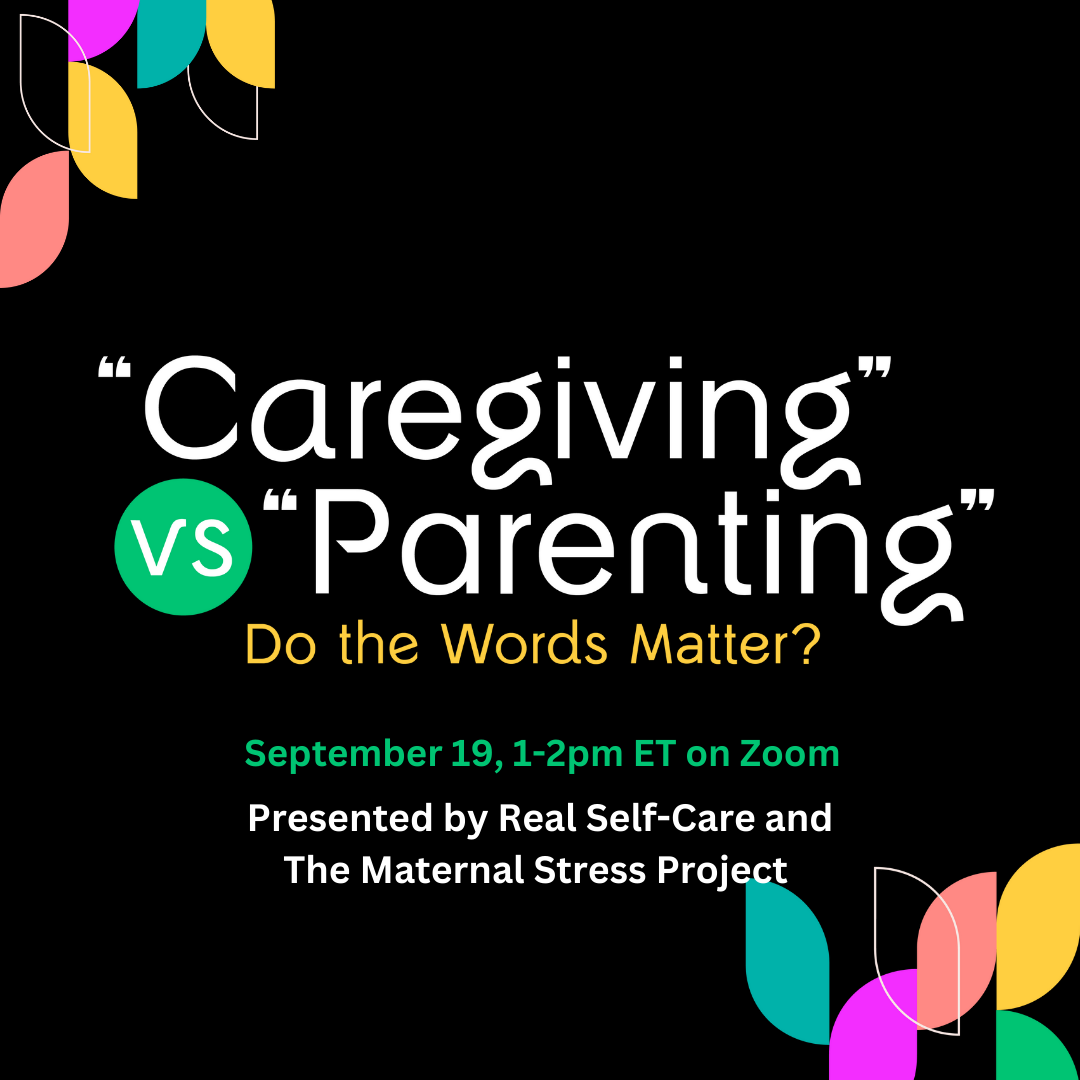

EVENT! “Caregiving” vs. “Parenting”: Do the Words Matter?

In conversation with Dr. Pooja Lakshmin, Sehreen Noor Ali, and Dr. Allison Applebaum.

To study the health effects of stress in a laboratory, researchers have a range of go-to chronic stress models to incorporate into their methods. They might repeatedly expose lab animals to a predator cue or force them to swim in a pool of water or let an intruder into their cage. They might mix it up with different stressors or timelines or contexts.

For humans, methodological options are a bit more limited. You cannot force someone to swim to points of exhaustion or ask them to fight off a rival in the name of science, so researchers look for other models to study chronic stress.

*Caregiving* is used in research as a human model for chronic stress.

Case in point, a research team investigating specific cardiovascular risks associated with chronic stress in humans studied mothers who were actively caregiving for children on the autism spectrum. As they note in their paper: "Caring for an ill family member is one of the best-established human models of chronic stress."

In the context of the maternal stress map, it seems like caregiving as a stressor could be a simple overlay. Every mother is exposed to this stressor if every mother is a caregiver1.

After all, it seems like the term “caregiver” has recently become interchangeable with the word “parent” across different media2.

But, is it actually the same?

The first person to plant this question seed for me was Dr. Allison Applebaum, a clinical psychologist and researcher who specializes in caregiver mental health and recently wrote about her own experience as a family caregiver in her book Stand by Me: A Guide to Navigating Modern, Meaningful Caregiving:

“We enter and exit caregiving repeatedly throughout our lives. Each caregiving experience shapes our stress experience.”

The stress of the caregiving experience is the thread to pull on here.

Lumping everyone (and every experience) together under one term relies on assumptions that flatten critical nuance in the context of caregiving, especially as it relates to stress. For example, as

points out in her excellent book When You Care: The Unexpected Magic of Caring for Others, there are joyful aspects of caregiving that may buffer the effects of stressful challenges during this time of life.But the joy is different too.

It is important to identify the different elements of stress and the different elements of joy — when caring for a baby vs. a child with medical needs vs. an aging parent vs. a friend with chronic illness — because those differences could impact how our body responds and recovers from stress or shifts into an unhealthy chronic stress state.

As Allison continued to explain to me:

“There's one difference that I think will need to play into [the maternal stress map]. The existential tone that drives caregiving. In all of the work I did to take care of my dad, I knew that he was going to die. I was blessed because he was my best friend but I knew that all of this effort and all of the love was qualitatively a different experience [than motherhood] because ultimately, when I was changing his diapers, I knew that he was going to die.

I think there's a protective component that motherhood allows for that caregiving for the medically ill doesn't. Motherhood is growth promoting – it is about helping to bring life in. Caregiving for the medically ill is often about helping individuals to leave this life.”

This comment made me reflect on an important distinction in how the human brain perceives and responds to stressors. Specifically the expected directionality of the challenge – “Is this getting worse? Or is this getting better?” The former scenario is a more potent stressor than the latter.

In the context of motherhood, what does it mean to be a caregiver?

How should we classify a caregiver and caregiving? And should we separate that experience from the labels of parent and parenting?

Another voice in my head as I toyed with these linguistic challenges came from

, who is a parent caregiver of a child with medical needs. Here is how Sehreen first explained it to me:“There is a difference between caregiving and parenting — a caregiver is someone who is responsible for the care of someone else, someone who has something chronic and ongoing. That is not necessarily a typically growing child. It's important to know the distinction because if you don't acknowledge the distinction, then we’re making a lot of people, who are living that experience, invisible.

If there's nothing out of the ordinary for your child beyond normal growth, that should just be considered parenting. For parents of children who need to have regular appointments or need regular interventions, there is an additional layer to your role: you are also caregiving.

I think the first instance of [feeling the difference in] ‘caregiver’ versus ‘parent’ was when I recognized the stigma parents face when you are not in a ‘normal’ situation with your kid. If there's something ‘wrong’ with your child (and I say that in quotes because I don't think any child is wrong), that’s on you. And it is usually the mother who steps into that additional caregiving role.

Caregiving is largely invisible and for the chronic caregiver, it's just so much more invisible.”

Where do we go from here?

I don’t actually have answers yet.

I have more questions. So many questions. My main questions, of course, center around how to peel apart the elements of stress – the sources, the connections, the buffers – related to the full view of a caregiving experience in order to better understand the potential impact of solutions.

To get to those questions, first we need to fully see and understand the distinction in experience that both Sehreen and Allison highlighted.

To start digging into it all, I’m syncing up with another brilliant and thoughtful human, Dr.

, alongside Sehreen and Allison, to have a collaborative conversation about this topic:Here’s a quick summary of the event:

The term “caregiver” has expanded dramatically in recent years. It now encompasses everyone from parents to those caring for an aging family member and those caring for parents, partners, siblings, children, and friends who live with chronic or life-limiting illnesses or disabilities. While broadening the definition has increased visibility for caregivers, it has also blurred the lines between distinct experiences.

What do we gain when more individuals identify as caregivers? What do we lose when we conflate the terminology around “parenting” and “caregiving”? This collaborative conversation will explore how interchangeable use of the terms impacts policy, workplaces, individual identity, and caregiver well-being.

Bringing together overlapping perspectives and individual journeys, our panel of experts include:

Pooja Lakshmin, MD – Reproductive psychiatrist and author of Real Self Care: A Transformative Program for Redesigning Wellness

Sehreen Noor Ali – Parent caregiver, co-founder of Sleuth, a crowdsourced insights platform for parents

Allison Applebaum, PhD – Clinical psychologist and researcher specializing in caregiver mental health, family caregiver, and author of Stand by Me: A Guide to Navigating Modern, Meaningful Caregiving

Molly Dickens, PhD – Stress physiologist, founder of the Maternal Stress Project

Together, we will delve into the nuances and potential benefits of more precise language while examining the unique challenges and rewards of both parenting and caregiving to foster a deeper understanding of the individuals who undertake these vital roles.

And that is not even taking into account the broader application to women, in general, who take on a bulk of caregiving for partners, family members, friends as they age or have medical needs.

Full acknowledgement that this category of caregiving is not currently reflected on the maternal stress map but needs to be. This statement seems to be a recurring theme (alongside my acknowledgment that the map needs to extend through perimenopause/menopause) and I promise to get on it soon!

Here is an example of this — an article in New York Magazine about Dr. Becky.

Dr. Becky is considered a parenting expert. The title of the article acknowledges that title but uses the term “caregiver” in the same sentence as “parenting”.

Is she talking to “parents” or “caregivers”? Does it matter?

Looking forward to this, Molly!