Cortisol is not your enemy

Not sure Ashwagandha will fix the effects of ripping away the social safety net.

“If we do this right, ‘stress’ as a word, will become an actionable term while we wait for the research to catch up. Especially in the context of women’s health.”

Words written over a year and a half ago and, whelp, we know where the “wait for the research to catch up” part is headed 🫤… so what about that first part? Is stress an actionable term yet?

Yes and no?

While I still think that “stress” is an inefficient word (especially when overused in the context of personal responsibility for stress management/reduction), I’m seeing more and more examples of applying it in the context of addressing broader social issues.

[hop down to the footnotes — 1 — for a few favorite examples]

As much as I would love to take credit for this, I wonder if it was just its time. The Surgeon General Advisory last August probably helped, even if it also did a crappy job of defining the term “stress” and some of the language and gender neutral approach pissed me off (c’mon, it did not specifically address the disproportionate burden on mothers despite citing several studies specifically looking at disproportionate burden on mothers. Sure, sure, I understand where it came from but…. c’mon!)

We still have work to do. In all the stress talk, especially in the context of women and motherhood, the thing that makes my skin squirm is when cortisol is thrown into the conversation in the context of negative health effects.

Stop blaming cortisol.

Or maybe I should word it this way: stop conflating ‘stress’ with high cortisol2. Or perhaps this (slightly more convoluted) way: stop making cortisol the key link between every stressful challenge of motherhood/ womanhood/ parenthood and the physical/ mental health effects that show up.

Please and thank you.

Ok, with that said, I understand the temptation to pull together some semblance of biological reasoning. The need to insert a how – how one thing affects another via stress. I get it. I love a good physiological how. I love connecting how one thing affects the other via the stress system. It’s kind of what I’m doing here – writing an entire Substack from the perspective of this exact how. BUT…

Cortisol is NOT the how to focus on.

Here is the issue that worries me: as soon as we name it and blame it, we put on the blinders and we narrow in on this one specific culprit for all our health woes. Then we look to “fix” that one thing and everything else gets off the hook.

You know who is ready to offer an easy way out for high cortisol? The wellness industry. Plenty of short cuts to combat cortisol. Plenty of opportunities to empty your wallet and avoid addressing the actual shit that got us in this mess to begin with.

When stress = high cortisol, we get sold all the potions and the foods and the supplements to “balance cortisol”, or “reduce cortisol”, or “clean up excess cortisol”3

Yes, cortisol is related to stress and it might even increase in these situations. Yes, cortisol affects a wide-range of systems across the body and can become problematic when dysregulated. It’s not entirely a misnomer to call cortisol the “stress hormone”. However, the role and concentration and rhythm in the body and a range of other factors controlling cortisol and the effects of cortisol is far more complicated than a simple reflection of an individual’s stress levels4. I'll spare you the physiology lesson on this (but feel free to visit this post if you’re feeling extra nerdy or just jump to the footnotes for a brief rant). I’ll summarize it this way: cortisol is one piece in a very intricate physiological puzzle and does not offer the full picture of what is going on across the body when exposed to chronic stress.

Even if cortisol is increasing from the stress related to any of stressors we might encounter on a daily basis, high cortisol is still NOT the thing to point to5. Chronic stress has wide-ranging health effects and not all of those long- and short-term effects relate directly to circulating cortisol levels. Pointing out the increased stress of these issues should be enough6.

Beyond the biological nuance, the more that stress is discussed in the context of high cortisol, the more we perpetuate that expectation that short cuts exist. The more we power the legitimacy of a wellness industry ready to offer “stress-reducing solutions” for our quick fix culture. Feeding off your instagram algorithm with amplified voices that ignore the source of the actual problems and instead offer tips for “hormone balancing”7. (

is one of my favorite humans calling out the BS of wellness and “self care” language with her push for and actual solutions).Avoid perpetuating and, most importantly, don’t buy into the distraction. This is more important than ever in 2025 America. We have a pseudoscience-devotee currently leading Health and Human Services who helped nominate a wellness grifter for Surgeon General, all operating under an administration that continues to demolish every ounce of stress-reducing support for parents/mothers/women/caregivers while piling on so much more stress. We are living under a government that is actively making us sick while putting people in power who might just tell America that we will be healthy again if only we all started taking Ashwandandha. I mean, who needs affordable child care or access to paid leave when you can take a coenzymatic B complex? 😒

With the dangerous combination of a wellness-leaning “MAHA” agenda with a government hell bent on cutting off anything resembling a social safety net, we need to be extra careful with the message. If the message comes across that the added stress of systemic failure and aggressive dehumanization is just a cortisol thing, are we going to have a national program to “balance cortisol” with Holy Basil?

Everyone loves a good short cut. I love a good short cut! But please please please, don’t lionize this short cut.

Here is my request:

Just say “stress”.

Or “stress load”. Or “chronic stress.” Or even “allostatic overload” if you’re feeling feisty. You don’t have to say “high cortisol”.

Let’s try it:

Child care instability increases stress exposure. (NOT: Child care instability increases cortisol.) Decrease stress exposure by stabilizing the child care system and expanding access and affordability to everyone. (NOT: Decrease cortisol by stabilizing the child care system and expanding access and affordability to everyone.)

Disproportionate mental load in the home can increase stress levels. (NOT: Disproportionate mental load in the home elevates cortisol levels). Reduce stress in the home by more equally dividing the cognitive and emotional labor8. (NOT: Reduce high cortisol by sharing the mental load)

Workplace issues related to work:life friction, discrimination, bias, and lack of support for parents in the workplace can cause stress (NOT: Workplace issues related to work:life friction, discrimination, bias, and lack of support for parents in the workplace can lead to high cortisol) Decrease stress in the workplace with culture shifts, flexible work options, and better paid leave policy for everyone. (NOT: Decrease cortisol levels…. Ok, you get my point)

Call it what it is: stress.

Then we can work on fixing it.

(and I’ll continue to connect the dots and fill in the biological how and health effects to counterbalance the over dependence on blaming cortisol. Join me!)

Examples:

Julie Kashen + team at The Century Foundation – Moms are Stressed. Congress Can Help. (Julie also has a great Substack with her friend, Traci Kirtley —

)- +

– A Heavy Mental Load is Breaking Down the Health of Women Living on Low Incomes

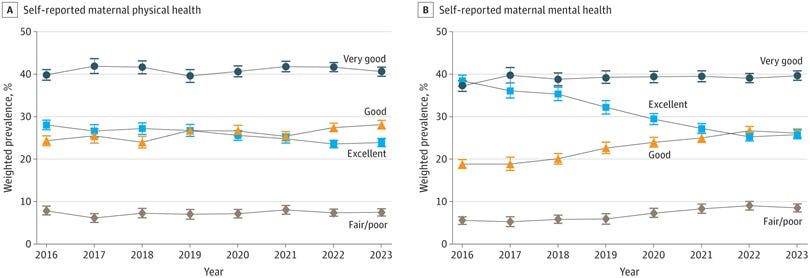

NYTimes coverage of the massive study showing that more women reported “fair or poor” maternal mental health between 2016 and 2023 – Study Finds a Steep Drop in Mothers’ Mental Health

Quick thing about that study though — Most coverage that I have seen about it tend to overemphasize the findings. It is an important topic and I am so glad to see it get coverage in this way BUT I think its important to point out the actual stats. The study classified perceived mental and physical health on a 5-point Likert scale (excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor) but ended up lumping together “fair” and “poor” into a four-point scale that ends with “fair or poor” because they had too few responses in the individual groups. An overwhelming majority of women actually classified their health as “very good” but “fair or poor” is the metric that matched the headlines, even though the change was pretty small (but statistically significant)— increasing from 5.5% in 2016 to 8.5% in 2023 — and most of the women in this range were single parents, had children on Medicaid, experiencing poverty.

The metric that I actually found more interesting was the switch between “excellent” and “good”. What is going on there?! Let’s talk about that one too!

Fun fact: The only diagnosable ailment that has the world “stress” in it — Post Traumatic Stress Disorder — actually has the opposite effect on cortisol levels. In patients with PTSD, cortisol levels tend to be lower than control groups or reflect no change at all; the differences between reduced cortisol or no change likely depend on sex and type of trauma experienced.

First of all, cortisol is a really important (and cool!) hormone and has a range of other roles in the body that have nothing to do with the stress. Respect cortisol, people!

Second, to think we have any control over the “balance” of hormones is overly simplistic thinking. With that said, if you are a supplement person and taking something (with absolutely zero risks) makes you feel better? Cool. It’s probably a placebo mind-body thing that (ironically) probably operates through the stress system by giving a sense of control. Still not a reason to make this a solution for everyone.

If you are one of the folks out there using a sensor, like an Oura ring or WHOOP, your “stress” is measured with heart rate and heart rate variability, which is reflective of your sympathetic nervous system. This is the fight-or-flight response not the cortisol response. But it is an interesting metric and may even be closer to what truly does change from day to day in terms of stress. Important to remember, you can have a fight-or-flight response without actually elevating cortisol. HRV is not a reflection of cortisol levels.

Also, when we have studies that show health impacts that may reflect the effects of stress without change in measured cortisol levels, we’re quick to say “but cortisol didn’t change.” That is problematic as well. There are many many MANY elements that change when and how cortisol is released and many factors that affect the way the cortisol signal travels across the body. If you take a point sample, there is a good chance that the measured concentrations of cortisol do not accurately reflect everything going on. What is measured in the blood does not necessarily reflect the available hormone in the blood (proteins called binding globulins affect that). Available hormone levels in the blood do not necessarily reflect the signal received (hormone receptors can change that). Hormone receptors do not necessarily reflect rapid and slow shifting changes in the signal (receptor dynamics, regional expression, and other factors can affect that). This list isn’t even doing it justice. There is A LOT going on with cortisol. It’s a messy metric.

Do you need cortisol to hit a measurable and significant change if there is a significant downstream health effect of whatever source of “stress” is studied? No. An outward expression of stress-related illness, significant changes in health outcomes (positive or negative) that can relate to stress should be sufficient, they tell a broader story. No cortisol measurement required.

And if it’s not, I’ll keep working on that one too.

not a thing.

This is fascinating and confirmed by 30+ years of neuroscientific research—both on parent-infant co-regulation and on how environmental stimuli affect the adult human stress system (HPA-axis functioning). Thank you for saying what needs to be said. Mothers need more social supports.

Anecdotally, my story bolsters your point: Here in Canada, we have a year of paid maternity leave (which was my most euphoric year of motherhood—possibly due in part to having tremendous levels of help from my husband whose work schedule accommodated his presence at home). But after that 12 months, my stress system became—for lack of better term—fucked. I'd never had a mental illness diagnosis (anxiety, depression etc) and was always considered very open and easy-going.

But after my daughter turned one, things took a drastic turn. I felt physically sick every day. I could no longer sleep, city sounds would send my heart rate through the roof, and I barely had the energy to play with our daughter—or walk 20 steps to the park beside our home without my hands shaking and stomach in a knot. With zero breaks, my allostatic load was immense.

I tried Ashwagandha, magnesium, inositol, everything. Nothing did a thing. For the first time in my life I thought I needed antidepressants or an anxiolytic. Though—as a former neuroscience of addiction reporter—I feared what starting those could do.

Then, after an extended trip to the grandparents' home out East, I realized something. I did NOT feel this way while there. I didn't feel like I needed anti-anxiety drugs because I didn't have anxiety. I had a normal level of care for our toddler, but not stomach-turning physical sickness and HPA-axis "cortisol cascade"-triggered insomnia. Able to watch her play with and ask for things from grandma, my heart rate slowed and I slept. On a smaller scale, when we invited other couples with kids over for dinner, I realized I felt better too. Their kids would entertain ours and she would forget about us for hours. Able to sit for a second and actually eat a meal, I could breathe.

What mothers need, as shown in multi-disciplinary research—from anthropology to psychology to neuroscience—is that the human brain before age 3 goes through rapid neuronal growth and so requires near-constant engagement. But not from an isolated, burnt-out mom; from a robust network of immediately-accessible social caregivers, who are familiar to that child and remain in that child's life.

In neuroscience 0-3 is considered infancy for reasons's of neuroplasticity/brain development. Warm, attuned parents and adult helpers who co-regulate an infant's own stress and emotions help build both their brains and stress systems in a healthy way. These social interactions grow resiliency in that child. Other multi-aged playmates who the child knows well help the parents meet the demands of their infant's unquenchable need for "serve and return" interactions—which are critical for cognitive and emotional skill development.

But in today's society—built around the nuclear household where one or both parents have to work to afford it—the environment we place both mothers and infants in, is so far from how we evolved for the vast majority of human history. And our neurobiology has not caught up to that rapid change, in an evolutionary sense. This isolation and burnout is causing significant harm to the health of both mother and baby.

In order to ease the incessant, chronic pumping of (such a deadly cocktail of) cortisol, adrenaline, and glutamate that destroy mitochondria and shorten telomeres, parents need tremendous levels of social help. They need social safety nets. What they *don't* need is to be told to "go get a hobby" or to put their "own oxygen mask on," (unless that advice comes with near-constant in-house help). What they need IS for professionals and pundits to educate the public (and policymakers) how urgent it is that social change happens. And for that, the public needs to know how utterly critical—both to a child's brain development and to a parent's healthy neurophysiology—social supports and communal help really are.

I love the footnote on how fitness trackers measure stress. I need to update all my posts with that info!